“Thickening the medium”: Material reorientations of the ‘witnessing’ stance in Divya Victor’s CURB the artists’ book

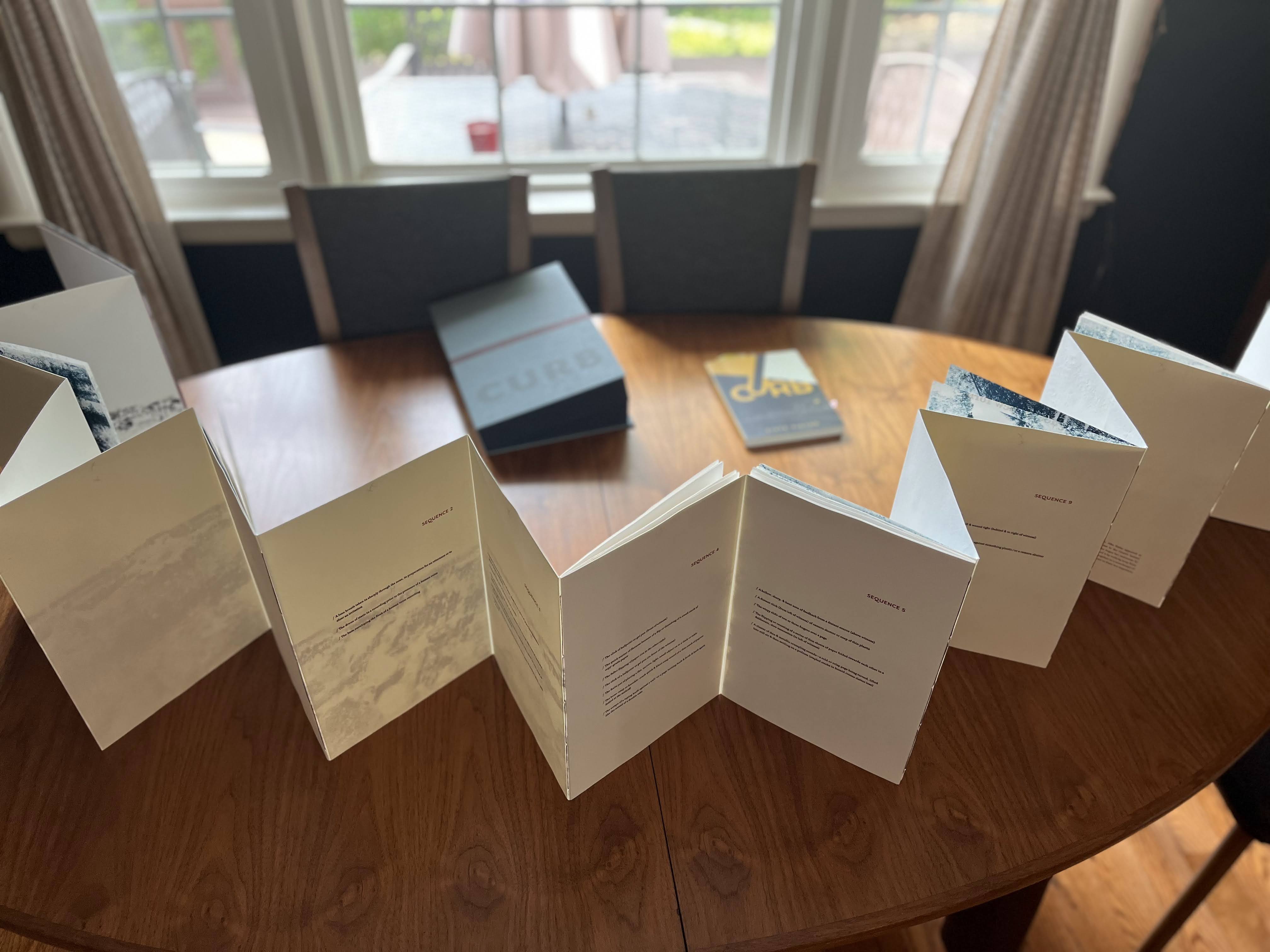

Figure 1: CURB the artists’ book, written by poet Divya Victor and designed by Aaron Cohick (2019), in an accordion fold-out (June 2023).

Divya Victor’s CURB exists, in one of its early iterations, as an artists’ book: poems are set on thick sheets of cream-colored paper, letter-pressed by photopolymer plates; pages are textured by rubbings of sidewalks and curbs; and lyric sections are sewn together with dark red thread. [1] The collection is designed as an accordion-style artists’ book [2]—featuring interconnected pages one can splay out across a table. Pages are double-sided, with foldouts and additional sections of poems sewn in. Text in the book was written by Victor, and the physical book was designed, printed, and bound in Colorado Springs in 2019 by NewLights Press artist-publisher Aaron Cohick, formerly of The Press at Colorado College (CC). Thirty copies were made in a fine print edition, including the book that I witnessed in-person in 2023.

CURB, which follows Victor’s poetry collection KITH (Fence Books/Book*hug, 2017), glints with reoriented cartographies—Degree Minute Second (DMS) coordinates “dog ear” the corners of various poems; and a digital “map” of CURB includes sonic and visual counterparts to poems: soundscapes, digital “poem-quilts,” visual art, and other collaborations. Poems in CURB examine hate crimes committed against the South Asian diasporic community post-9/11, paying attention to the quotidian “curb” as a site of brutal violence. As a polyvocal documentary poetry collection, CURB embeds a range of languages and documental forms [3] within its pages, negotiating overlapping geographies and histories of empire that surround racialized violence in the U.S. Even as poems in CURB are seared with the grief, fear, and rage of South Asian immigrants and their kith across suburban curbs and other landscapes, these poems also gather sensorial moments into garlands of care: the wetness of breath, dried “feathers on the clothesline,” “sari pleats pulsing like flushed gills,” an Uber driver headed towards the East Village, where he pulls up “next to an ailanthus tree / growing from a wall, its roots / a delta spreading / on red brick,” as the speaker considers the possibility of kith: “there is an us / forming” (Victor CURB 123; 21; 39; 70; 69).

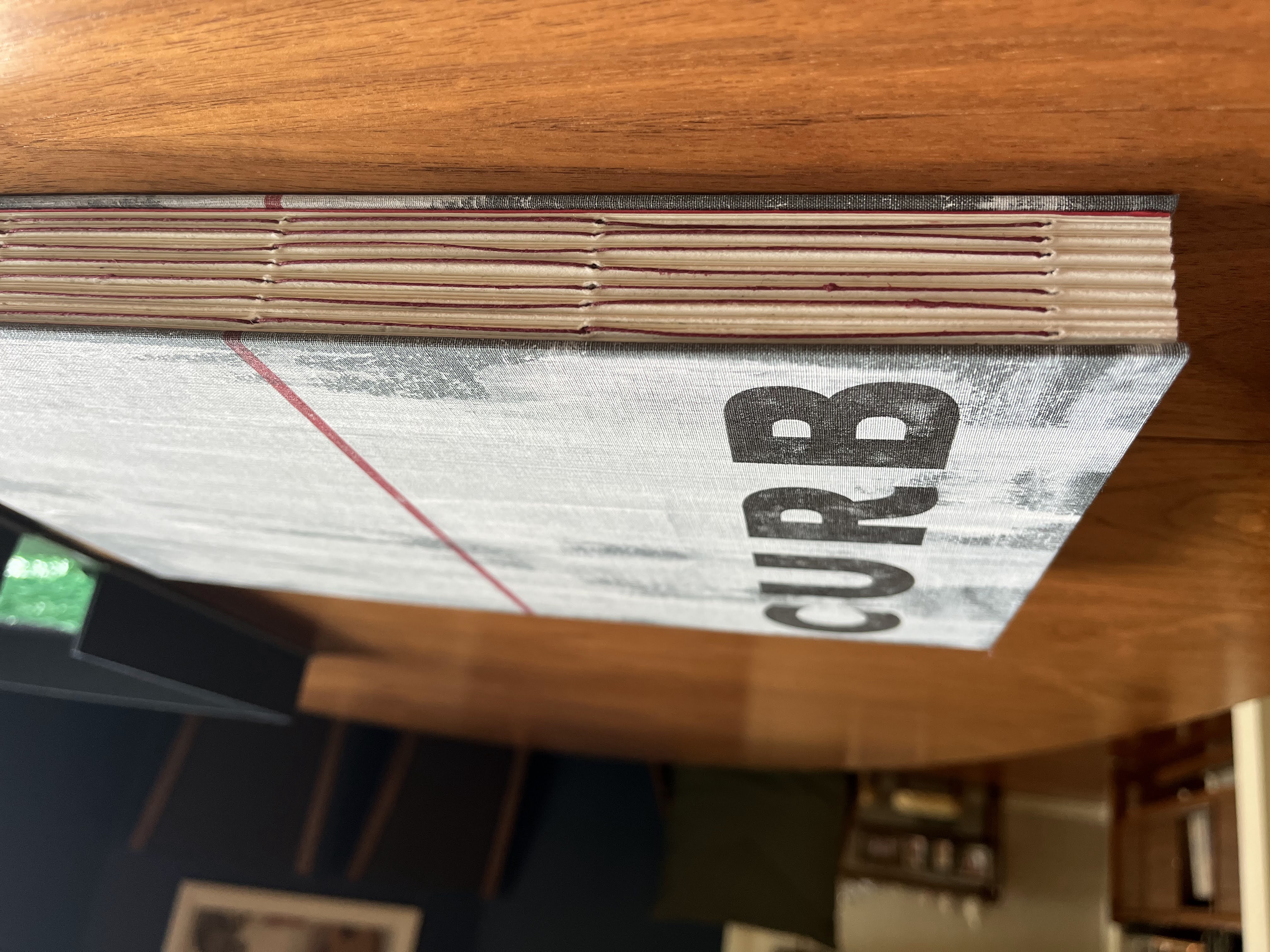

In 2021, CURB, the full-length poetry collection, was released in a print edition by Nightboat Books. Victor writes, in the book’s dedication: “This book was made to witness the following irreducible facts: these men once lived; they lived; they were loved; the United States of America is responsible for the force of fleeing and action that ended their lives. May their names never be forgotten.” [4] In this essay, I linger with the word witness as a provocation for thinking alongside the artists’ book where CURB first emerged. How might the act of poetic witness expand within a multimodal, material context?

Figure 2: CURB the print book, released by Nightboat Books in 2021, with the artists’ book (The Press at Colorado College, 2019) box in the background.

Since Carolyn Forché’s popularization of a “poetics of witness” to the North American reading public in 1993, [5] an increasing number of contemporary documentary poetry collections have been described by critics and readers through the lens of “witness.” Such critics frequently point out how poems of witness may testify to and memorialize often-violent histories, allowing readers to empathize with the subjects of distanced pasts. Forché described “poetry of witness” as poems that occupy social space, poems that “bear trace of the extremity within them” and provide “evidence of what occurred,” referring to the extremity of traumatic and violent events often experienced firsthand by poets themselves (30).

Yet in our contemporary “attention economy,” where the image circulates at high speed and pressurizes each act of looking, poets such as Cathy Park Hong have expressed skepticism at the implications of a virtuous witnessing stance, exploring how, as Hong writes, “Images of suffering can arouse our horror, simulating an illusive identification between us and the victim or ‘a fantasy of witness’ before we are conveniently deposited back into our lives so that someone else’s trauma becomes our personalized catharsis.” Hong warns of misplaced proximity, wherein readers may risk overidentifying with subjects in a documentary poem, so much so that they fail to consider their own important distances and differences from the subject matter at hand.

Rather than prompt fantasies of identification with poetic subjects, CURB the artists’ book returns our readerly attention to the important distances that separate reader, from speaker, from author. The recognition of such distances, says Victor, is important. Without it, the poem of witness risks re-enacting “an almost direct re-wounding of the reader or re-establishing of identity so aligned with the victim, that the reader is not, in the process, able to contemplate their own complicity; they’re not able to contemplate their own different position in the vectors of power” (20:46). The multimodal possibilities in CURB reorient the ‘witnessing’ stance—focusing on important somatic and structural materialities that invite a slowing of attention, and space for critical reflection in one’s reading: How am I (we) implicated in this?

In this essay, I point to specific ways that CURB the artists’ book is attuned to and generatively expands the poetic witnessing stance through the multimodal. I ask: How do contemporary documentary poets, writing post-2020, newly occupy and reinhabit poems of witness, beyond Carolyn Forché’s initial framework of a poetics of witness producing “trace” and “evidence” of a prior event (30)? What can a practice of multimodality invite into a documentary poetry “of witness”? And what new forms of reading might be opened up through multimodal attention to “revivifying” [6] the witnessing stance? I study the aesthetic and material strategies enacted by Divya Victor’s documentary poetry collection CURB (Nightboat Books, 2021), in its artists’ book format (The Press at Colorado College, 2019). Through a close exploration of CURB the artists’ book, and through conversations with its creators, poet Divya Victor and printer-artist Aaron Cohick, this essay wanders towards new material invocations of poetic witness that call for somatic attention, distance, and a focus on what Victor has termed “effortful reading.” [7]

The aesthetic argument of color

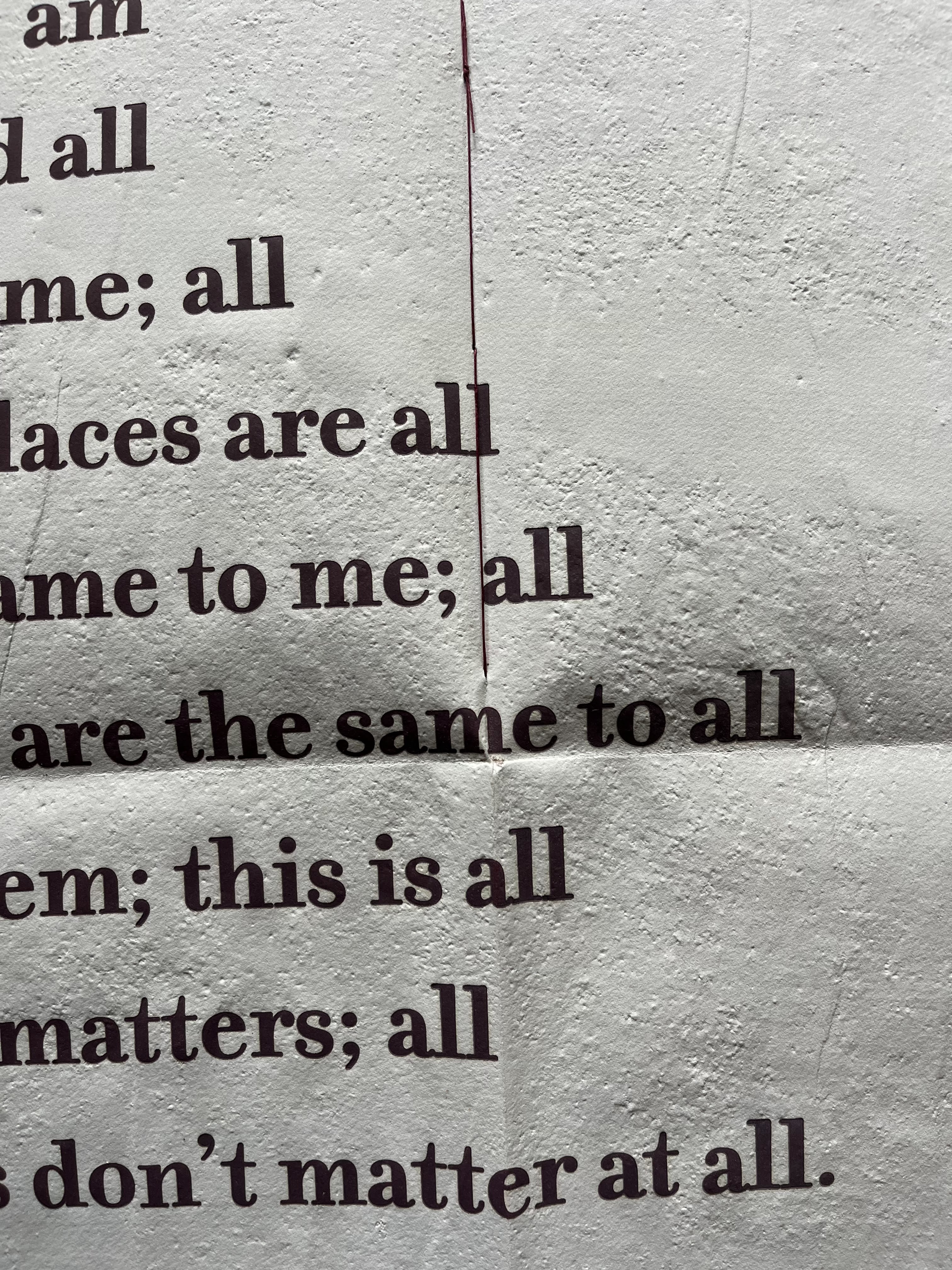

I first encounter CURB the artists' book in the summer of 2023. The book sits in a clamshell box with its title etched on the cover; a red line extends through the middle of the box face, a red that reveals itself in the book’s cover pages: dark and wondrously clotted, and then again in the hue of string that appears between the seams of pages. Instantly, I think about Victor’s introduction to CURB, wherein the speaker, naming her fear in response to anti-South Asian violence, describes carrying her child in a small wagon “painted Cinnabar or Hemoglobin.” The speaker notes: “We are dragging all that blood around / in the afternoon with the fear / set soft in limbs roving the sidewalks…” (1). Red, red, black, white, blue. These are the hues of the artists’ book, real and smooth, textured in my hands, which pulse with blood as they turn the leaves of pages.

Figure 3: An up-close shot of CURB the artists' book, when closed. The book’s clamshell box and green bubble-wrap are in the background.

Color was an important consideration in the making of the artists’ book CURB. As Victor and Cohick describe in our interview, the color palette of the artists’ book offers geospatial connections. Victor tells me how indigo, a color that infuses the artists’ book, also associatively conjures the native plant of Michigan, where Victor currently lives, and where some of the poems [8] in CURB take place. The color indigo, an early color “of ink and dye,” geospatially links Indigenous presence in Michigan with a history of colonial export from India, and further draws figurative links between author (Victor) and printer (Cohick) (22:32). Vermilion red conjures “the color of blood spilled on concrete,” but it also makes associations with the sindoor: the red dot, “a symbol of the seed, a source of life” on the foreheads of South Asians (Victor 51). These colors, associatively linked to physical environments and their histories, highlight geospatial attention as one important dimension of the book.

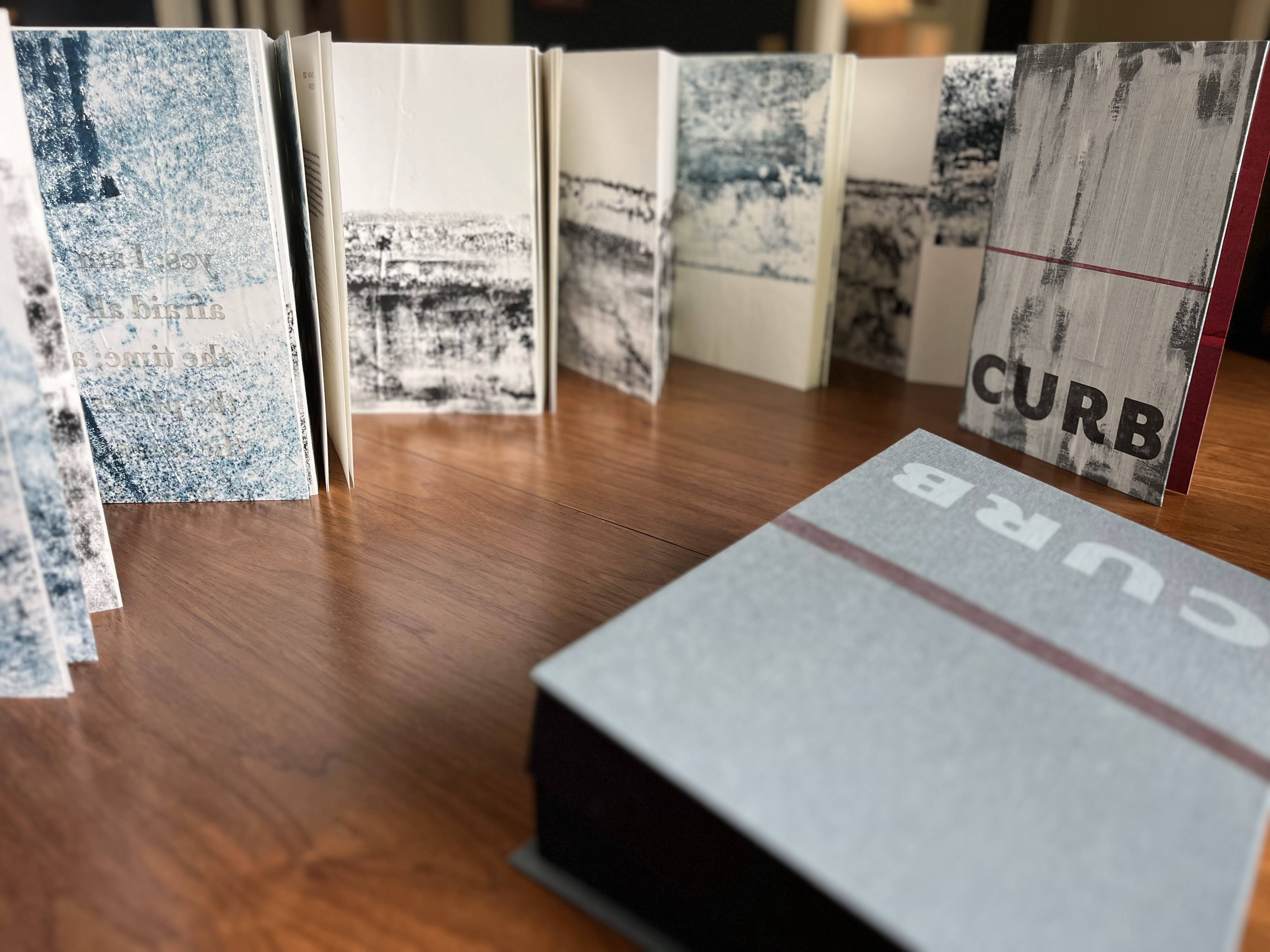

Figure 4: An up-close shot of a page in CURB the artists' book, where red ink is overprinted with gray.

Vermilion red also carries an embodied aesthetic argument. As Cohick writes in the artists’ book’s colophon, “The red text of the poems was overprinted with gray multiple times—once for each of the people that this book is dedicated to,” [9] which explains the darkness of the red hue—a red that is continuously run over, again and again, by the imprint of lives that its language gestures to. Red ink, in many ways, bears a similar resemblance to fresh blood; the overprinting of gray suggests a drying out, a wound that has scabbed over. Jerome McGann discusses poetic texts as “thicken[ing] the medium as much as possible—literally, to put the resources of the medium on full display, to exhibit the processes of self-reflection and self-generation which texts set in motion, which they are” (14). CURB the artists’ book, by way of performing its visual poetics through medium-based choices such as overprinting red with gray, “thickens” Victor’s poetic argument, which asks readers to consider the weight of fear and trauma inherited by South Asian diasporic communities living in the United States. For each word that Victor writes in honor of the lives of those lost, red ink bears, quite literally, the gray weight of those losses.

Accordions and foldouts

Figure 5: An up-close shot of CURB the artists' book—the backhand side of the book features rubbings from sidewalks and curbs; the clamshell box sits in the front of the frame.

The book’s structural shape offers another form of geospatial attention. The artists’ book, which takes an accordion shape, can be propped upright and spread across the entirety of the table. Positioning the book this way allows for a reader to somatically orbit around the rubbings of physical sidewalks and curbs as they fan throughout the book, in an alternating sequence of black and blue.

To read across the whole book, I begin moving my body around the dining table, walking back and forth past the text, hearing the floorboards creak as I circle the pages. Victor has described this reading experience through its “kinesthetic movements, […] a kind of dance around reading,” where “the whole body becomes implicated in the reading process […] one has to bend, move, lift one’s arms, walk around the table, sit down…” (31:50). For me, this somatic “dance” has the effect of slowing down my reading experience, inviting a hyperawareness of each word pressed across the page, and an attunement to each bumpy tracing of pavement.

Victor describes another intention behind the artists’ book’s rather unwieldy, large design:

When you open [the artists’ book] up, it can take up an entire dining table. These vertical sections open up like massive maps, because I was thinking very much about the post-1965 move to the United States that many South Asian Americans undertook, and how they would have to engage in map-reading all the time to find their way around everyday places. Reading maps in public spaces is one of the most pronounced ways before the digital era where you would announce your place as a stranger. It’s this conspicuous act of reading that then allows others to read you in that public spot. The book started enacting some of that conspicuousness and effort in navigating public space. So, [the artists’ book] started as that. (Victor, “Coalition in the Imaginary”)

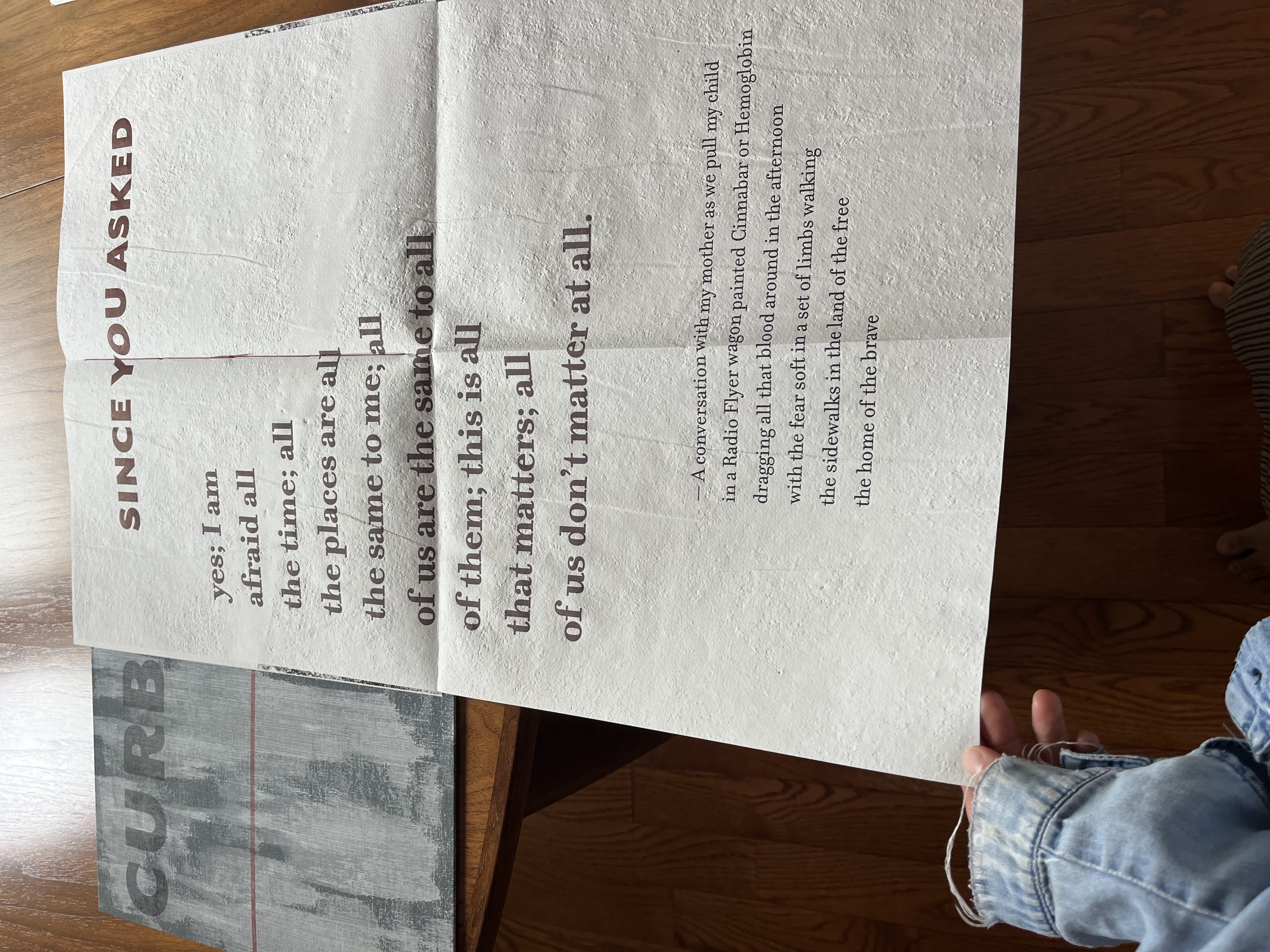

Figure 6: An up-close shot of the foldout poem titled “SINCE YOU ASKED,” in CURB the artists’ book.

Victor emphasizes reading maps in public space as a marker of one’s foreignness; the map orients its reader to a location, but in doing so, it also signifies a reader’s body as vulnerable in a public space. [10] The artists’ book is hyperaware of how reading operates on textual, geographic, and bodily levels, and it enacts this awareness of reading through its material form. Rather than including foldouts of geographic maps, CURB the artists’ book includes foldouts of poetic language that acknowledge sites of violence, fear, and kinship. Handling each foldout poem thus brings to mind the unfurling of a paper geographic map. By encountering these foldouts within the artists’ book, the readerly stance shifts—moving from our expected left-to-right reading orientation, to down the page.

Thwarting the parasitic function: Effortful reading

To modulate distance and proximity throughout poems in CURB, Victor foregrounds “effortful reading” in her poetics, which she defines as a reading practice “tethered to choice, volition.” When I asked Victor to expand on her conceptualization of effortful reading, she described the practice as laboring to read on one’s own terms:

To be able to choose challenge; to be able to choose struggle; to choose effort, rather than have effort thrust upon you and the coordinates and the constraints of effort thrust upon you, whether that's through a labor contract, or the conditions of your workplace. To really say, I am going to take an hour to sort this poem out, because this now is my time. (04:48; italics my own)

In CURB, effortful reading involves infusing each poem with many different material, somatic, and multimodal portals for the reader to inhabit—what Victor calls “multiple exits…multiple egresses from a poem, especially poems that are about such difficult histories” (31:31). The emphasis, Victor says, is for readers to be able to exit the poem, especially a poem that is about difficult, violent historic material, in many different ways: “If we cannot leave [...] if we can’t find these multiple egresses, then we’re trapped inside the poem’s rhetorical shape. [...] And I’m not interested in holding the reader in that rhetorical hermetically-sealed rhetorical shape,” she said (31:31). Rather, Victor prioritizes an approach of readerly agency, which includes opening up multimodal portals and expanding the ‘shapes’ that one’s reading can take—rather than read linearly, a reader is invited to return, depart, and return again to a poem, shifting directions of reading towards a sort of recursive engagement.

Effortful reading offers a spatially expansive mode of reading, one that transcends “hermetically-sealed” edges of a poem compressed by singular form and constrained in image and content. Victor uses effortful reading to move a reader away from the “alienated language use” of “dead text,” the language of assent in meetings; everyday small talk; and emphatic discourse—all formulaic languages that involve less intention or choice (Victor “Personal Interview” 04:48). Such “dead text” has an automated, lackluster quality to it. Rather than communicate, dead text seems to endorse what’s already been said, requiring little energy or presence. Effortful reading, meanwhile, promotes a kind of aliveness and awareness to our experiences with language, sparking attention to the contexts and liberatory possibilities of language use. “To choose effort in decoding an exegetic practice is like a great freedom for me,” Victor explained. “It's reading as a practice of freedom, to echo Friere and hooks. And that's where, in my life, I have found myself the most myself in effortful reading” (04:48; italics my own).

Victor’s reference to “reading as a practice of freedom” lives in the spirit of Paolo Friere’s and bell hooks’s pedagogies, which suggest the possibility of reading as a means of self-actualization (hooks 15). Victor implies that effortful reading produces a counter-landscape to the terrain of “dead” language; effortful reading can enliven a text and infuses it with agency, action, and the attempt to engage within and on the reader’s own terms. This possibility is important when considering the subject matter of CURB, which reckons with white-supremacist, racist violence against South Asians, and the possibilities of kithship (and distance) in the aftermath of violence. A reader has choices to engage critically with this material, as well as choices to leave.

Victor’s reference to the “deadest of languages” strikes me as especially poignant for considering the documentary poetry genre, which relies on poetic context to reposition and often elucidate the material, social, and emotional reductions of bureaucratic language. In our interview, Victor described the “parasitic” nature of the bureaucratic document:

My relation to the dead text of a bureaucratic document is about finding [...] the kind of sinew and the artery that is still connected to that text. It’s not fully dead. But… where it attaches to the body, that discovery is what the poet needs to make. Where does it still remain attached and tethered? There is an umbilical relationship. That is, it functions much more parasitically if you don't turn it into a poem, because a bureaucratic document aims to be a parasite on your biography. And to siphon from you the pith and the essence of what makes you you. And to reduce it. [...] So then, the poet must return to the reduction and to say: There is an expansiveness here that I want to give back to what this document annihilates. (10:33; italics my own)

From this definition, the poet’s role is to reconstruct the embodied self “annihilate[d]” by bureaucratic text, to search for the point of connection between “dead text” and living body. Victor’s use of embodied language such as “sinew,” “artery,” and “umbilical” suggests the crucial presence and weight of the human body for reading, recording, and making sense of flattened bureaucratic script—a human presence that is often obscured or diminished by bureaucratic paperwork. The documentary poem is positioned as one way to disrupt the “parasite on your biography,” turning from an abstracted document back to the rhythms of specific breath, of specific flesh, of specific life. Rather than allow bureaucratic language to “siphon” and “reduce,” Victor’s poetry warps bureaucratic text by reimagining, writing over, and even regenerating original “dead text.”

In CURB, Victor reimagines bureaucratic forms such as Form I-130 (Petition for an Alien Relative) and the “Civics (History and Government) Questions for Naturalization Test” by incorporating sensorial and tactile details—such as in “Third Petition,” when the speaker interrupts the Form I-130 checklist to breathe:

I am filling out this petition for my (Select only one box):

☐ Spouse

☐ Parent

☐ Brother/Sister

☐ Child

☐ I am filing this petition during the third shift at the Mobil, I am filing a petition for her eyes & her tendency to leave jars open That will be $4.50 Have a good one. I am filing a petition for her eyes & her tendency to leave jars open & the way a nape turning away from me That will be $17.80. Have a good one. I am filing a petition for her eyes & her tendency to leave jars open & the way a nape turning away from me is a bride walking towards me, her hands veiled in a vermillion epic written with a crushed branch of henna Yup, you’ll find it right next to the coffee. Yup. Have a good one [...] During the third shift, you do not see her as I do, between the Haribo Gummies & the Sour Cream Ruffles: fluorescent, arms akimbo; sweet burrow; sweetest sparrow. (Victor, CURB 43)

Victor disrupts the parasitic form of the state-created document by contrasting two registers of “dead text” with sensory memory. A body at work, a body in service, a body trained into the automated language of the cash register: “That will be $4.50. Have a good one,” “Yup. Have a good one,” a body compressed into a relation on a checkbox (“Parent,” Sibling, “Child”), is also cast as a body “walking towards me, her hands veiled in a vermillion epic…” The descriptive language of the body, illuminating a nape, her eyes, her hands, also blurs into “parasitic” dead text, creating the effect of a skipping tape: “& the way a nape turning away from me That will be $17.80. Have a good one [...]” Yet the sensory images of the body continue to interrupt the automated script of the register, pushing forward and accruing atop one another to form a more complete portrait of “the way a nape turning away from me is a bride walking towards me…” Rather than allow dead text to leech into the body, the speaker insists: “you do not see her as I do,” using poetic text to burst outside of the bureaucratic frame. The poem itself invites the reader to re-see beyond the reductive lines of the documental petition and its classifying mechanisms; to thwart the function of the petition as a mode of efficiently “establish[ing] the existence of a relationship to certain alien relatives” by slowing down skimming to a process of effortfully reading such relationships across the page.

An origin in effortful reading

Registers of distance are continuously enacted throughout the artists’ book—including through the book’s lack of instructions for how to read and handle its pages. Given CURB’s attunement to the specific power of the paper document in a human world, I am hyper-aware of my own body as it touches the spine of the book, then rotates the paper body on its back. Initially, when I face Victor’s artists' book, I am fearful to dive right in. I’m scared I’ll tear something, smudge or break the pristine pages. The book, snug in its clamshell box, is at first a mystery to me. I cannot tell where the seam gives way to an opening, and I rotate the box around a few times before gently prying the hinge—like an oyster shell—to release. Inside, the artists’ book is wedged beneath a sheath of green bubble wrap. The book itself is a heavy weight in my hands, materially beautiful in a way that I pause to admire: its red-seamed spine, certain with even stitches; the sharp edges of each carefully-cut page; a textured rubbing hinting at the grainy sidewalk someone pressed paper to, letting public space leave its trace. I’m reminded that this book, in particular, was passed and made through a series of hands, and it is now my hands that hold the book gently, pulling it out of its box and laying it flat across the table; it is my hands, too, that touch the grainy feeling of pages rubbed over curbs, recalling, in myself, the childlike desire to run a bicycle wheel up and down, up and down the hinge between sidewalk and street. I think, here, of Jill Magi: “This is the significant part of the power of the book; the link between paper and skin is known. In order to continue inside a book, readers must hold the page, lift, and turn. So they are quite close to whatever content is delivered, and they literally hold this content in their hands” (Magi 274).

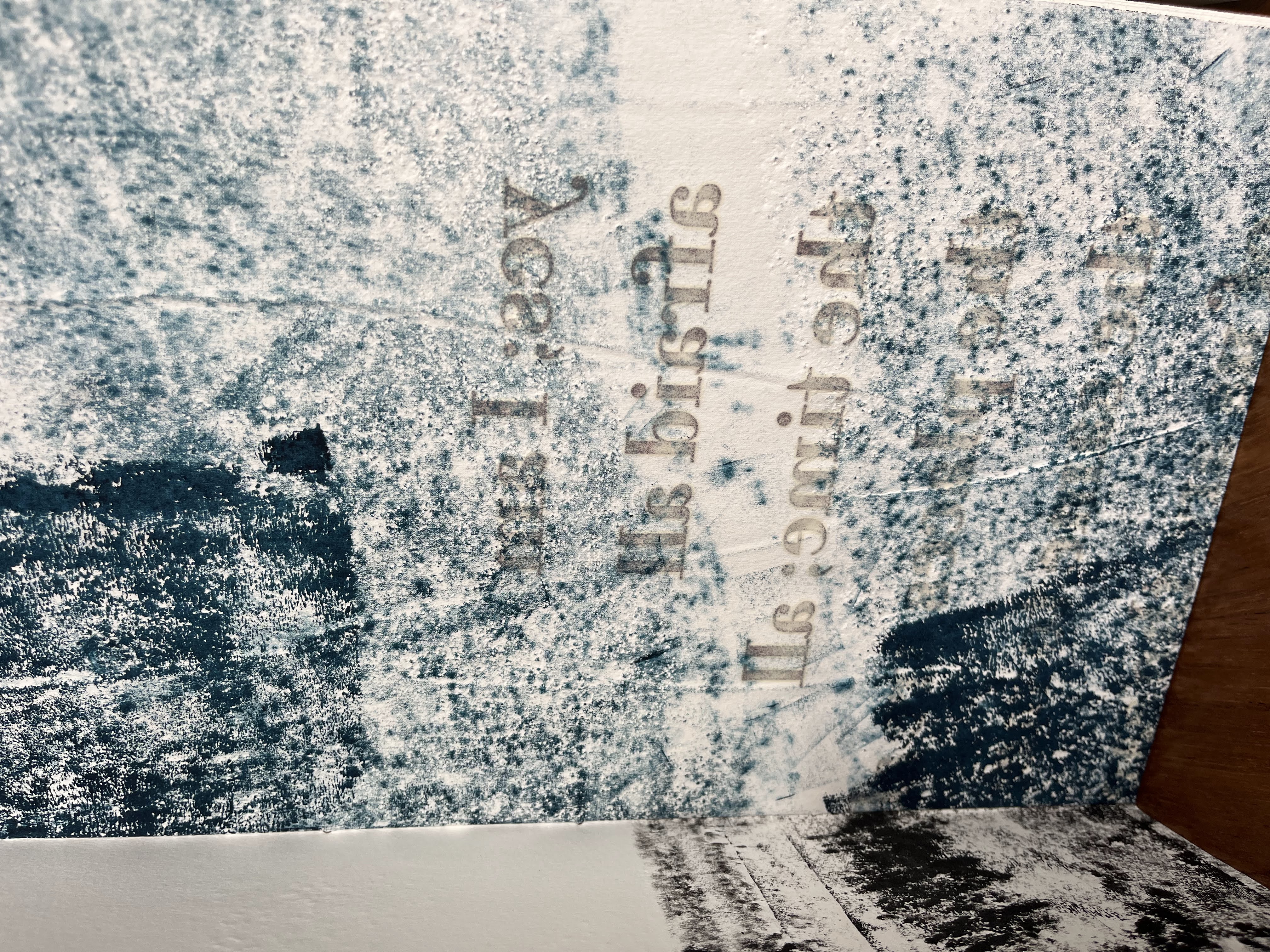

The artists’ book itself does not carry instructions for engagement. Rather, the reader herself is invited to hold the book in her hands and interact with it in various positions—reading the book one way (accordion style) versus another (flat on the table). Sewn-in sections of the book are not self-explanatory in terms of their usage. The eye, roving over the book, might glance over text hidden behind pages; the eye might misrecognize or even skim over. For example, as I arranged the book upwards, fanning it around the table in an accordion, I noticed what appeared to be backwards text faintly emerging through the pages. As the window’s light cast itself through the book, the backwards text “yes I am afraid,” appeared, almost as a shadow behind textured rubbings of sidewalks and curbs. Upon examining the book more closely, I realized that the “backwards” text was, in fact, a part of a foldout spread that required me to pick up the page and unfold it, thus witnessing the beginning of a new poem unfurl.

Figure 7: An up-close shot of a sidewalk rubbing on a page, with the text “yes; I am afraid…” imprinted on the back.

Victor and Cohick discussed their interest in designing the artists’ book as an ambitious reading experience. They wanted to create a book that would incorporate “misreading, difficult reading, effortful reading,” in order to reveal how “misrecognition is fatal” (Victor “Coalition in the Imaginary”). Victor’s focus on “misreading” acknowledges how bodies may be read and misread in public spaces, resulting in material and physical consequences. And while the implications of “misreading” the artists' book may not be fatal, misreading the artists’ book still has consequences for one’s understanding of the poems. For example, to ignore the foldout pages—“SINCE YOU ASKED”—would be to disregard key moments in the book that point to the speaker’s own relationship to fear, her bodily and emotional experience of the assaults described, and her ethical negotiations of relating to the people to whom the book is dedicated. Focusing on “misreading” as a part of the book design also suggests the possibilities of the artists' book as a kind of body that is maneuvered, negotiated, and judged in real time.

“Frequency,” a rhizomatic spine

Other poems in the artists' book offer nonlinear, effortful approaches to reading through their material shape and form. One such poem is “Frequency (Alka’s Testimony),” which the viewer can read by standing the book up accordion-style. The poem “Frequency” follows the assault and eventual death of forty-nine year-old research scientist Divyendhu Sinha in 2010. Sinha was beaten into a coma by strangers in their New Jersey neighborhood while on a post-dinner walk with his wife, Alka, and their two sons (Victor, CURB 114). At the hospital, he later died of a hemorrhage. His attack occurred on the street where he and his family lived.

Victor’s poem “Frequency” pays tribute to the eight-minute-long testimony that widow Alka Sinha offered in the New Brunswick Superior Court in August 2013, in which she described witnessing her husband’s death. In the YouTube video of the testimony [11], Alka, an immigrant woman, can be seen reading from sheets of paper stacked in front of her on the table, at times glancing up to face the judge, other times stumbling over her words and re-starting sentences. As Victor noted, “It was important to me that we pay attention to this image of a woman reading in a juridical context,” referencing Alka’s tactile gestures of “moving her hands delicately across the script” [12] of her reading notes while testifying. Victor describes Alka’s movements as “this bodily practice that we sometimes retain from childhood when we are trying to learn a new language,” indicating the importance of each word on the page, and further paying attention to Alka’s body—an immigrant widow’s body—in negotiating the language of the courtroom. She adds: “The preciousness of every single word in Alka’s testimony—I wanted that as my charge when I wrote CURB” (Victor “Coalition in the Imaginary”).

In “Frequency (Alka’s Testimony),” [13] Victor creates a sequence of ten interlinked “frequency” poems [14] that draw attention to the sounds made throughout the courtroom during Alka Sinha’s court testimony, pointing to the relational networks of sounds—living and dead—that comprise the ecosystem of a courtroom, an atmosphere that often comes with a set of bureaucratic scripts, temporalities, and presumed sounds. Without focusing on Alka Sinha’s direct speech, each page of the long poetic sequence notates a “frequency” of other sounds—such as paper flipping; a camera shutter clicking; the wet intake of breath—that permeated the courtroom during Alka’s testimony (129).

During my interview with Victor and Cohick, Victor described the distinction between “bureaucratic time versus lived time,” acknowledging “how immigrants really relate to time and attention.” Referencing the bureaucratic location of the courtroom or the state’s immigration services, Victor pointed out a kind of “bureaucratic reading…you are scanned; you’re in a system and you’re moving; [and] as an individual, you’re processed. So what is poetry doing to counter bureaucratic temporality in reading?” Victor asked (38:17). If the experience of bureaucratic time is measured in how much time it takes for “bureaucrats and machines to read the immigrant,” then Victor conveyed the “lived experience of bureaucratic time” as an excruciating experience. “Imagined bureaucratic time alienates you from perceptual time,” she said. “And both those types of attention to time exist, in contrast to bureaucratic time, which is lightning fast for reading the immigrant” (38:17). While “bureaucratic time” can feel both painfully slow and fast at the same time, simultaneously too compressed and too extended, “perceptual time” pays attention to the lived experience of such time on human bodies.

“Frequency” focuses on gestures of interference that may disrupt the experience of bureaucratic time—one such example is Alka’s decision to play Sinha’s voicemail recording at the beginning of the court proceedings, an action of intimate sonic care in a location where such care is often absent. Sinha’s voicemail greeting not only interrupts bureaucratic time, but it places a listener (and reader) more thoughtfully within perceptual time, by sounding the somatic rhythms of breath, stuttering, and voice—all living dimensions enfleshing a bureaucratic system.

Complicating the courtroom’s typical role as a geospatial location where procedural paperwork and testimony are privileged, the artists’ book form and design of “Frequency” places readers in proximity with encounters—and resistance—to bureaucratic time. Positioned as an accordion-style poem that spans multiple pages of the artists’ book, “Frequency” invites the artists’ book’s viewer to move with each “sequence” of the poem. Cohick notes that he took inspiration from Victor’s conceptual framing of the poem “Frequency” as the “rhizomatic spine” of the book (15:57). The idea of a “rhizomatic spine” inspired Cohick’s foldout accordion structure, which underwent multiple iterations before its current form. Instead of turning the pages of the book from left to right, the accordion-spread can be rearranged into a circle, thus offering each sequence as linked to the next. When spread across the table, one can see the stitched connections between sounds in the courtroom. Throughout “Frequency (Alka’s Testimony),” human speech is portrayed in red ink, while non-human sounds (paper shuffling; ballpoint pens clicking) remain in black text. One sequence describes a “frequency” of such sounds:

f The click of ballpoint or gel pen (in front of witness)

f The quick scatter of flatness because of a flip or

thumbing of a small stack of copy-grade paper

f The fuller flipping of paper (on to the other side)

f The click of a ballpoint or gel pen (in front of the

witness)

f The finite pat of placing a flat, narrow, light, small

object on to a desk or table

f The bone-snap or knuckle-crack quick & blunt

sound of a thin stack of papers folded at the midriff

f The scrape of a taping knife against a wall /or a page

turning back & forth & back again like the sound of a

double take (Victor, CURB 121)

Victor’s poem lingers on the physical environment of the courtroom, and on the sonic textures that leak beyond Alka Sinha’s testimony. As the poem alludes: in a courtroom, where bodies cannot reenact trauma or violence, other bureaucratic objects—stacks of paper, the “scrape of a taping knife,” a wall—might perform their own sort of sonic violence.

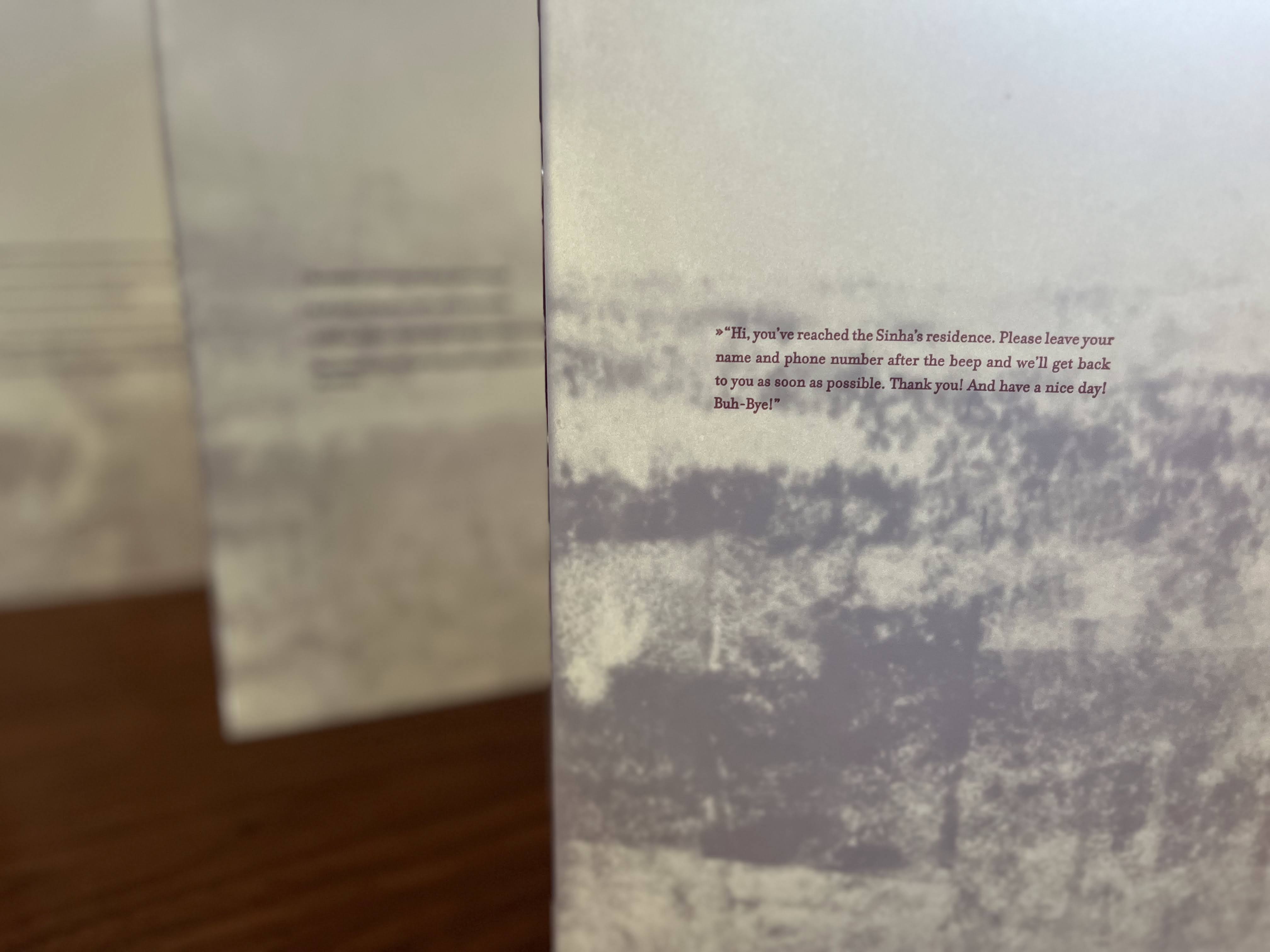

At the end of the poem in the artists’ book, Cohick and Victor have included the transcription of Divyendu Sinha’s voicemail. The voicemail re-captures Sinha's voice in its living form, overshadowed by gray ink:

“Hi, you’ve reached the Sinha’s residence. Please leave your name and phone number after the beep and we’ll get back to you as soon as possible. And have a nice day! Buh-Bye!”

As Victor noted of Divyendu and Alka, “His recorded voice & her living voice were buried together in a soundscape of this courtroom” (116). Yet, rather than “bury” Divyendu’s voice-mail greeting beneath other sounds in the poem, the artists’ book centers his words at the end of the poem. Notably, Divyendu’s last three lines in the voicemail: “Thank you! And have a nice day! Buh-Bye!” give the reader a glimpse of his living voice, a glimpse that is not seen in the Nightboat Press 2021 edition of the poem.

In the context of Alka Sinha’s testimony in court, paper has authoritative agency—a material context that cannot be ignored when touching the papery edges of the artists’ book. Paper, as Victor implies in the poem “Frequency,” carries a verdict and a sentence; documents witness accounts, perform legal transactions, keep records of past events, and signal what’s to come. The artists’ book version of “Frequency,” comprised of hand-stitched, folded paper, encourages readers to activate our listening to the frequencies of material gestures—emphasizing the connections among the courtroom, the power of paper, the genre of the testimonial, the “rhizomatic spine” that orbits our physical readerly movement around the violent and intimate sounds reverberating within the poem.

The textual condition

Through this essay, I’ve explored how the collaborative artists’ book iteration of CURB uses material interventions to prompt somatic attention and reorient the pace of reading. These material invitations invite readers to consider reading poetry as a somatic encounter, one that leaves weight, texture, and sensory traces on the witnessing body, and that, as artist-publisher Aaron Cohick poignantly put it in our interview, allow the reader time to “get out of … habituated modes of attention” (36:20). The artists’ book makes space for readers to attend to the weight, spatiality, and somatic consequence of carrying poetry “of witness” in one’s body, a body that is, importantly, distant from the poetic subject described in the text.

CURB the artists’ book is what initially drew me to write about Victor’s work. I’m interested in the possibilities enmeshed not only in reading a poem, but in experiencing it, touching it, designing it, folding it, tasting it, tracing it, paying new forms of attention to the poetics of space, pace, the sensorial, and form— what Jerome McGann has written about as the relationship between poetry and textual material:

The object of poetry is to display the textual condition. Poetry is language that calls attention to itself, that takes its own textual activities as its ground subject…poetical texts operate to display their own practices, to put them forward as the subject of attention. That means, necessarily, that poetical texts—unlike propaganda and advertising texts, which are also highly self-conscious constructions—turn readers back upon themselves, make them attentive to what they are doing when they read. (11)

What Cohick describes as “habituated modes of attention,” McGann pinpoints as a hyper-awareness of reading as labor and as embodied experience: “[attention] to what [we] are doing when [we] read.” CURB the artists’ book leans into the vibrations of sound, the textured bump of a sidewalk-rubbed page, the accordion foldout long poem, the vermillion red darkened with ink—all instantiations of an effortful reading practice. In this way, CURB the artists' book also “turn[s] readers back upon themselves” through its material forms, which encourage readers to interact with the pages, to participate in movement, and to consider the implications of color, texture, and shape of words as they perform upon the page.

In recent years, there’s been a rise in documentary poets, including Victor, whose projects live within the multimodal and, in my mind, who shift the stance of poetic witness more towards readerly processes that invite participation, distance, difference, effort, time. In addition to CURB, I think of Craig Santos Perez’s from unincorporated territory series (Omnidawn Press, 2008-2025, and ongoing); Paisley Rekdal’s West: A Translation (Copper Canyon Press, 2023); Don Mee Choi’s DMZ Colony (Wave Books, 2020), as a few examples.

Notably, CURB the artists’ book was a collaborative effort between writer and publisher-artist. During our interview, I was moved to hear Victor respond to Cohick about the tactility of moving from textual poem to material artists’ book within a collaborative context. Victor said:

It’s like, you hold a world or a house in your mind, and that’s really heavy. And then someone comes along and they say, You can actually settle it down, because I know the materials in which you can house this… the concretization of ideas in the material fact of the book is really important for poets, poets like me, anyway. [...] Concepts are too heavy to hold for one person. And collaboration is like two people carrying a concept in order to materialize it. [...] For me, I experienced it as a somatic giving away of what I had to hold. (22:32; italics my own).

Victor’s descriptions of material relief, [15] “a somatic giving away of what I had to hold,” and collaboration as “carrying” all offer important lenses through which to read the artists’ book. Poetry, as Sarah Dowling describes, can “run interference on the every day.” A collaborative project such as this artists’ book offers generative interference: stretching the ways we might be habitualized to read and create, animating new forms of sensorial attention, ultimately reorienting our modes of “bearing witness” through the multimodal.

Notes

[1] These rubbings were created by “hammering the damp sheets of paper onto the concrete with a brush, then rolling them with screenprinting ink.” See: CURB (The Press at Colorado College): https://www.thepressatcoloradocollege.org/curb

[2] When closed, the book measures 12.5 x 8 inches, but when fully extended, the length of the book measures up to 13 inches.

[3] These documents range from immigration paperwork, such as Form I-130, Petition for Alien Relative, to navigational directions in a Los Angeles Uber ride.

[4] The book honors the lives of Balbir Singh Sodhi, Navroze Mody, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, and Sunando Sen, all of whom were immigrants, or children of immigrants, living in the United States (Rhodes).

[5] Following Forché’s edited anthology, Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness (W. W. Norton).

[6] The language of “revivify” in this essay is indebted to CURB letterpress-printer Aaron Cohick. During our interview, when asked about how he thinks about reading and designing experiences of reading for the artist book CURB, Cohick said: “...how any sort of structure or printing or texture or textile, or any of that stuff sort of fits together to [...] revivify attention is really, really important to me” (36:20).

[7] The term “effortful reading” is Divya Victor’s and will be explored more in-depth later on in this essay.

[8] Poems such as “Lawn (Temperate)” and “Beds (Clay)” contain dog eared DMS coordinates that reference various locations in Michigan (Victor CURB 20, 23).

[9] The artists’ book is dedicated to twelve different South Asian victims of murder and assault; the re-printing of ink “transform[s] the act of printing into a mourning/meditation that manifests as an excess and literal blurring of the text,” writes Cohick (“Aaron Cohick and Divya Victor, CURB.” The MCBA Prize. https://mcbaprize.org/aaron-cohick-divya-victor-curb/ 2020.)

[10] As Victor notes, this “act of reading […] then allows others to read you in that public spot.”

[11] Victor’s poem specifically references the YouTube recording of the trial, which features Alka Sinha’s testimony.

[12] The line “a childhood habit of tracking the traffic of glyphs / across oceans” in “Pavement” refers to Alka Sinha’s reading practices. This “tracking” in CURB also gestures towards the deliberateness of each individual word in each poem, especially considering that these poems move through a multiplicity of languages— English, Latin, Hindi, Gujarati, Malayalam, Tamil.

[13] Victor’s own audio recording version of her poem “Frequency (Alka’s Testimony)” can be heard at the PennSound archive.

[14] Accompanying the “Frequency” sequence is Victor’s own collaborative auditory composition, as published on her website “MAP OF CURB(ED).” On this website, there are a host of supplementary resources that accompany the poetic book, including an audio collaboration with artist Carolyn Chen to the poem “Frequency (Alka’s Testimony).”

[15] Victor said: “As a poet [...] We’re just managing signs; we’re just…working in the sky, [in] mid-air all the time, in high concept worlds where really intense emotions are being negotiated. So when Aaron began to speak about materials—paper, thread, cloth, concrete inks, metal parts, wood, right—these concrete materials, they came as such a relief to me.”

See here for a complete list of works consulted.