The Iterative Environments of Juan José Saer: On Nobody Nothing Never and The Event

The most prominent trait of Juan José Saer’s writing, I’d argue, is precise, dare I say “geometric,” descriptions of people, places, and events—almost ad nauseam, almost as if the world is unfolding in slow motion, including sentences and phrases we might call linguistically filtered descriptions, propelled by refusal to cut to the chase and make something happen. Another characteristic trait of Saer’s writing is repetition, which is most pronounced in his novel Nobody Nothing Never: scenes, descriptions of landscape, dialogue, sentences, phrases, etc, repeat, sometimes verbatim, across the novel. The combination of these two traits makes for novels in which, for the most part, nothing really happens. They can be kind of…boring? Or painful to read for the impatient. But they’re also strikingly beautiful, and these features—the insistence of stillness, lack of narrative “progress”—are central to the concerns of the narratives the novels work through. It’s not refusal for the sake of it, or perhaps not a narrative refusal at all.

I’ve been reading Saer’s fiction periodically over the last fifteen years, most often returning to Nobody Nothing Never, and I published a review of the most recent translation of his work into English, the novel The Regal Lemon Tree, but I haven’t yet said what I want to say about his work—though I’m not entirely sure what that is. I’m interested in a quality of Saer I find both unique to his work and a little puzzling—that is, his descriptions of landscape—in hopes that this might shine a light on his fiction (and my interest in it) more broadly. My other motivation is my sense that Saer is wildly underrated, at least in the U.S.

For the purposes of this essay, I will focus on two novels: Nobody Nothing Never, originally published in 1980, and The Event, originally published in 1988 (the English translations appeared in 1993 and 1995, respectively). The “plots” of the two novels are as follows:

- In Nobody Nothing Never, a man named Cat

lives in a small house by a river. It’s February, “an unreal month,” and it’s

very hot. A friend brings a horse to stay on Cat’s property because multiple

horses in the community have been killed—someone is going around shooting

horses. Cat is supposed to keep an eye on the horse. His girlfriend comes over;

they have sex and drink white wine. He lies on the cool tile floor. Horses

continue to be murdered, Cat watches the horse in the yard, people swim in the

river. That’s about it.

- In The Event, which takes place in the

late-19th century, Bianco (not his real name) has fled Europe. Bianco

was performer claiming to be both telekinetic and telepathic, and a group of

scientists and a journalist dressed as a clown called him a fraud then drove

him out. He has since moved to Argentina and purchased land for ranching and

brick-making on the pampas (plains). He travels back and forth to town to see

his pregnant wife Gina who helps him practice his telepathy in hopes of making

a grand return. But he suspects Gina is purposely disrupting their experiments

and possibly having an affair with his business partner and that the child is

not his. If he’s really telepathic, though, none of this would be a problem.

There’s also a pandemic.

Both Cat and Bianco ebb and flow around and in meticulously described environments. They both are often described as still, not moving—and little “happens” in the traditional sense. There’s not even much dialogue.

So I’d like to try to make sense of the environments these characters inhabit. The landscapes are written in such a way that the construction of the landscape in writing, in the form of narrative, is front and center. And the painstaking description paired with repeated / looped / iterative / recursive moments of landscape or domestic interior occlude the characters’ and the novels’ pull toward sense, reason, and action. Whereas in a novel like Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy, which does something similar (Nobody Nothing Never is surely an homage to Jealousy—in Jealousy the narrator becomes disembodied by his obsession—about another extramarital affair—almost turning himself into a camera eye); here, instead, Saer’s protagonists (in varied points of view within the respective texts, to boot) are prevented from seeing what they want because they’re seeing something else. Or rather, or also, readers can’t see much at all because there’s possibly nothing to see other than the environments they’re turning inside. The environments, in a sense, prevent the mysteries from being solved.

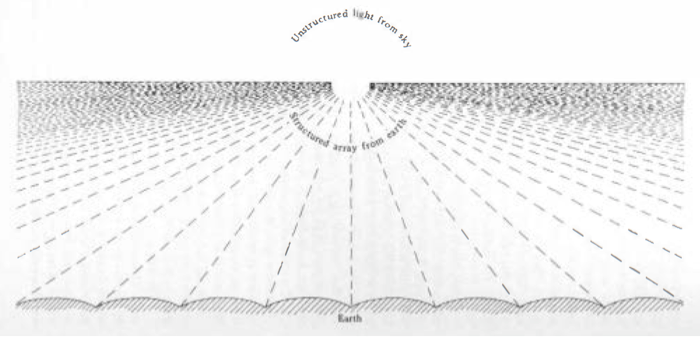

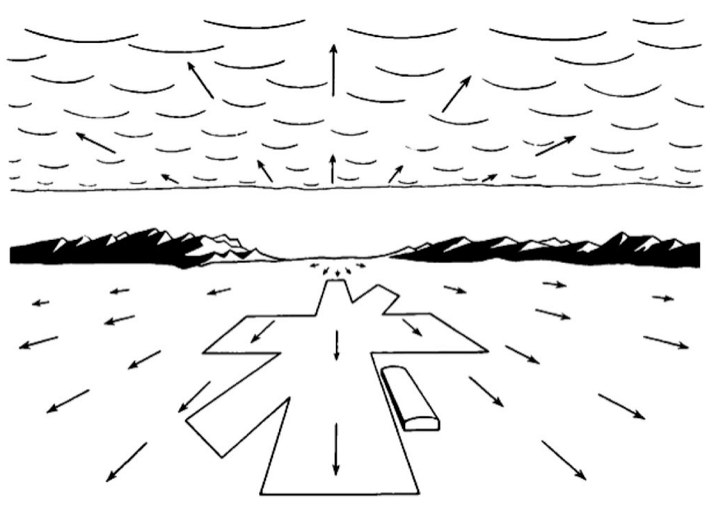

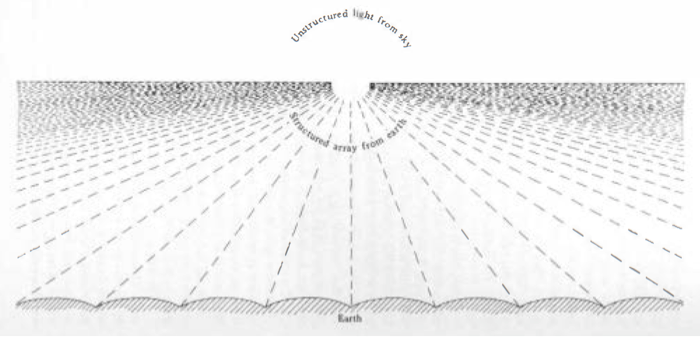

Before getting to environments depicted in prose, I want to ask: What do people see when they see? It’s an old question—but more often the question concerns how rather than what. Maurice Merleau-Ponty takes up this idea in texts like “Eye and Mind” and The Phenomenology of Perception where he notes that “Nothing is more difficult than knowing precisely what we see” (59) and “We see only what we gaze upon” (“Eye and Mind” 353)—something that seems obvious but maybe isn’t? In this research I also came upon a couple treatises on perception, from the 1950s-ish, by the psychologist James J. Gibson, one of which is called The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception and is peppered with images like this:

which quite frankly looks like an illustration for The Event as Bianco repeatedly stares out at the horizon line at the edge of the pampas. Gibson aims to define not just how but what—and why—we see what we see—in natural environments specifically. He lists tools and terms for describing these environments and repeatedly uses the word “information”: what type of “information” does our visual perception in a particular location yield? What gives and what hides “information”? If you recall my brief plot summaries, what’s missing for the protagonists is simple information: who is the murderer, is there an affair or not. There are some specific concepts from Gibson that I believe are useful in interpreting Saer’s descriptions, particularly his understanding of information. The others include what he calls an “ambient optical array”; the specific role of light; what’s revealed or concealed; the units or edges of things and how they “nest” according to scale; how we communicate what we perceive; the “ghost” of geometrical purity; and “events” as “disturbance[s] in the invariant structure of the array.” Here, Gibson offers categories of environmental seeing; his approach is a method of explication, a kind of exploded view for a language of landscape.

First: The Event

In The Event, Bianco takes possession of a large portion of land where he’d like to raise cattle, and he is also in business with a new friend to manufacture and sell both wire fencing and bricks. The latter two ventures work nicely for imagining Gibson’s spatial structures. But let’s just look at a few examples of Bianco observing the pampas.

Bianco lowers his head once again and begins to scrutinize the horizon in the direction from which [a flock of birds is] coming, and it seems to him that he sees, at the very point where the earth and the sky join, a minuscule spot, flattened and moving, like irregular and nervous strokes made with a pencil so as to clumsily efface a horizontal line. Intrigued, he stands stockstill, observing the mobile scribbling which, standing out a bit on the horizon, disturbs its smooth emptiness. (7)

After a while (fourteen pages during which there is a flashback), the “scribbling” moves close enough that he can see it’s a herd of horses which he then describes as a series of things including a single mass, an “archaic clay of being,” “a cosmic wind,” “divided into an indefinite number of identical individuals,” “an infinity of stars,” and “a row of poplars” (21).

In this moment, we see the edge of something, the horizon line, as a background for two kinds of animal movement: the birds flying toward him, and the herd of horses, which at first he sees only as a pencil mark “scribbled” against the geometric purity of the horizontal horizon. The scribble’s disruption of the “smooth emptiness” of the plane/plain simultaneously evokes something static, an event as described by Gibson as disturbance, and the trouble of describing what we see—

—the “ambient optical array” of the pampas is defined by the edge of what can be seen, and an expectation of stillness, the expectation of pictographic landscape, twice fluttered. This also highlights Bianco’s attempts at description, or the narrator’s, via pencil marking—the drawing of what’s seen, the construction of an image, the image’s change in shape through perception. At the same time the image is (kind of) constructing itself. It refuses to settle or be named—even though we know it’s a herd of horses, the multiple descriptions of the herd is yet things other than a herd of horses, which prevents the transmission of information that we might typically find in a description of an environment. We’re not looking at the grass, the sky. We’re looking at something impossible to see.

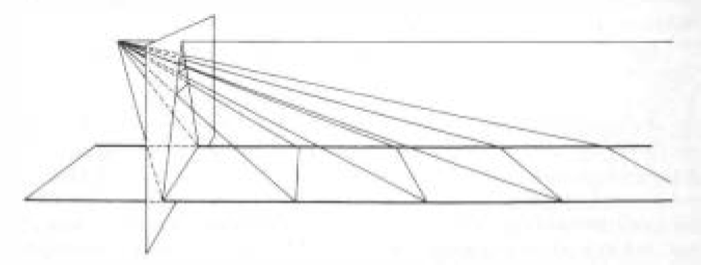

We also see Bianco negotiating edges of environments, what can and cannot be defined as he moves through them, and like the pencil, this moment is likened to the drawing technique of perspective:

The cognac boils in Bianco's brain, as he sees, from astride his horse, a horizon that has retreated, toward which the vacant lots, the vegetable gardens, the scattered houses, the trees, the badly designed streets of sandy earth lying between the grass growing in the ditches and in the cracks of the almost nonexistent sidewalks, as they fade from sight in vanishing perspective, become immersed in a denser and denser haze of sultry heat, which, although it is transparent enough not to conceal them completely, by blurring their contours somewhat and making their volumes vague and fuzzy, confers on them a sort of unreality.

Here, Bianco is noticing designated spaces marked geometrically by edges and lines, but each of these spaces is vacant, absent, or blurred.

The cognac boils in Bianco's brain, as he sees, from astride his horse, a horizon that has retreated, toward which the vacant lots, the vegetable gardens, the scattered houses, the trees, the badly designed streets of sandy earth lying between the grass growing in the ditches and in the cracks of the almost nonexistent sidewalks, as they fade from sight in vanishing perspective, become immersed in a denser and denser haze of sultry heat, which, although it is transparent enough not to conceal them completely, by blurring their contours somewhat and making their volumes vague and fuzzy, confers on them a sort of unreality. (148)

This form of repeated negation abounds in The Event and even more strongly in Nobody Nothing Never (which you can tell by the title), often landing on the word “unreal” or “unreality.” The horses running across the pampas are too amorphous to be real; they must be something drawn, fabricated. The “unreality” of the environment is most often due to heat: the heat shimmers over the ground, sweating, “boiling” brains, and so forth. The environment is oppressive not because it’s physically restrictive but because it’s so undefined.

Near the end of the novel, Bianco’s wife Gina is about to give birth in their house out on the pampas where he spends much of his time—he knows every inch of it, has made a concerted effort to be enveloped in it. Recall that he’s suspicious of her for two reasons: one, he thinks the child is not his, and two, he thinks she might be messing with his experiments in telepathy. The novel traps him in not-knowing. He steps outside:

On the pampas nothing is moving, there is not a bird, an animal, a cloud in sight, there is no breeze blowing, and the tawny grass that is so soft that it collects in compact clumps beneath Bianco’s boots has no sheen in the unreal, ashen light… I am now in an empty space, gray and beige, in which nothing is happening…

During the first six days nothing happens, except for the gray sun that slowly crosses the gray sky, the absence of sounds, of a breeze, of anything alive on the pampas, apart from the two of them… Bianco looks out at the heavy rain that since noon the day before has never once stopped falling. The flashes of lightning and the thunderclaps have been less noticeable, more remote, farther apart. A greenish light, which is neither semidarkness nor bright daylight spreads out in more and more compact folds moving farther off in space, and there is no sky, or earth, or horizons, nothing, only that greenish, uniform medium in which the cabin seems to be floating or to have been deposited, as at the bottom of a fish bowl. (185-7)

If nothing happens here, nothing can happen to him? He’ll remain suspended; he’ll never know. Not knowing is a sort of form of control: refusal to or inability to see the landscape because of whatever strange light and fog, whatever total absence he’s experiencing outside. His recognition that the things he knows best are not there reinforces his literal or metaphoric occluded vision, not only his failed telepathy but the landscape in front of his face. This refusal, as highlighted by the fish bowl as container, is a form of control, I think. He’s got Gina there in a space she can’t leave and where nothing can happen: he’s forcing a lack of event.

Second: Nobody Nothing Never

Maybe what I’m getting at is simply negation, erasure, writing that undoes itself. Gibson’s insistence that geometry is ghost is apt here: that there’s no point, no line. In an environment you have edges, light and shadow, only what’s perceived, and that perception is tied to the perceiver as they move through it, as they look, what their eyes fall on, and how they register and name a thing. Saer’s undoing, giving and taking away, is strongest in Nobody Nothing Never in which not only do we have an excessive amount of descriptions that are “unreal” where there is “nothing,” but these descriptions repeat, loop across the book—nothing multiplied. But there’s not nothing happening: there’s sex and drinking and boats and murder. Cat’s inability to sort this out, or the narrator’s—Nobody Nothing Never does shift back and forth from third to first person, always with Cat—also creates a kind of suspicion: but not his, ours. Who is killing horses? I’m stuck in the book as it refracts and echoes, a mise en abyme of a book, truly, that begins and restarts with the same launch. I could call it recursive, technically, and maybe not be wrong:

In the beginning, there is nothing. Nothing. The smooth golden river, without a single ripple, and behind, low-lying, dusty, in full sunlight, its bank sloping gently downward, half worn away by water, the island. (7)

In the beginning, there is nothing. Nothing. The smooth golden river, without a single ripple, and behind, low-lying, dusty, in full sunlight, its bank descending, half worn away by the water, the island. (13)

In the beginning there is nothing. Nothing. The smooth golden river, without a single ripple, and behind, beyond the yellow beach, with its windows and its black doors, the roof of Spanish tiles reverberating in the sun, the white house. (54)

In the beginning there is nothing. Nothing. On one side of the smooth, golden river, without a single ripple, the island with its bank that gradually slopes down to the water, the stunted, dusty vegetation, on the other the two windows and the black door, the roof of Spanish tiles, the white house, and in between the empty stretch of yellow beach, sloping almost imperceptibly down to the river, on which the sunlight, like a huge yellow conflagration traversed by white filaments, flows, rebounds and reverberates. (87)

In the beginning, there is nothing. Nothing. The deadly quiet streets, deserted, roasting in the sun and up above, parched, ashen, without a single cloud, full of burning slivers, the sky. (133)

In the beginning, there is nothing. Nothing. The smooth, golden river, without a single ripple, and behind, low-lying, dusty in the nine o’clock sun, its bank descending gently, half eaten away by the water, the island. (176)

There is, in the beginning, nothing. Nothing. In the light of the storm, in the imminence of the downpour—the first one, after several months—, things take on reality, a relative reality doubtless, which belongs more to the one who describes or contemplates them than to things properly speaking: the white house, with the enormous trees that bury its side wall in shadow, the open space of the beach, the sparse trees downriver, the grills, the slope that goes up to the sidewalk, the low-lying island whose slope descends gently, its edges all eaten away, toward the water, the smooth river, without a wrinkle, polished and steel-colored like a motionless sheet of metal that reflects the steely sky. (208)

It’s a little interesting (but maybe not the most interesting thing in this work or here) that the last examples I’m giving from both of these books are about rain: rain as blur, rain as about to come creating a stillness that is more real (“reality”) than any moment in the book so far (always “unreal”).

In another novel, The Regal Lemon Tree, fog does this ghostly work: fog and water form as spaces for memory and terror, the undefined equal to dream state and a kind of mania. Why repeat the book’s opening, continually evoking nothing? It reminds me of a moment from Thomas S. Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in which he insists that discovery is not a single act—that you figure something out after iterations, accumulation (55, though this is one of the main premises across the text). At the same time, the constructed nature of these repeated lines across Nobody Nothing Never (and these are not the only repeated lines, moments, and scenes, though they might be the most pronounced) brings us back to the scribbled horses. The horses are an extension of the horizon line as it’s drawn; mutated descriptions layer each other, occluding the herd itself.

In contrast, Gibson’s interpretation of such “occluding edges” groups this phenomenon alongside superposition, objects perceptually in relation to each other as a kind of cinematic wiping, hinting at the appearance of simultaneity in quantum states. He writes:

There is a disturbance of the structure of the array that is not a transformation, not even a transformation that passes through its vanishing limit, but a breaking of its adjacent order. More exactly, there is either a progressive decrementing of components of structure, called deletion, or its opposite, a progressive incrementing of components of structure, called accretion. An edge that is covering the background deletes from the array, an edge that is uncovering the background accretes to it. There is no such disruption for the surface that is covering or uncovering, only for the surface that is being covered or uncovered. (83)

It’s the horizon line that’s disrupted, whatever is in the distance, not, say, the horses running in front of it—they’re whole and fine. In Saer's environments the line stays what it is, a geometric fixity; the pampas are there even when it feels like they’re not. But in the iterations of “In the beginning there is nothing,” what’s disrupted is not an object occluding the landscape, but the language describing it: the construction of the description filtered through the troubled perception of a slightly anxious narrator. The fact that this kind of jarring, forceful nothingness is repeated is both an accretion and a deletion of information as defined by the edges of the thing defined, the edge of the visual field being described, the limits of vision. But at the same time it’s about the edges and limits of text to say what something is—and there can’t be repetition with an edge or end.

Works Cited

Gibson, James J. An Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Psychology Press, 1986.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. “Eye and Mind.” The Merleau-Ponty Reader, edited by Ted Toadvine and Leonard Lawlor, Northwestern UP, 2007.

---. Phenomenology of Perception, translated by Donald Landes, Routledge, 2013.

Saer, Juan José. The Event, translated by Helen Lane, Serpent’s Tail, 1995.

---. Nobody Nothing Never, translated by Helen Lane, Serpent’s Tail, 1993.

Note: A version of this paper was delivered at The Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture Since 1900 in February 2022.