On Erica Baum’s Dog Ear

Erica Baum’s Dog Ear provokes questions of how tactile engagement with and manual manipulation of text can rupture and generate meaning. It asks the reader how they might read a poem through touch, and how that might be different than reading it through sight. Jacket2 describes Baum’s collection as demonstrating reading’s physicality, as dog ears render “new [sites] of meaning [...] (appropriated, deformed) by the reader’s hand”. [1] Because Baum’s folds often cut through characters, distorting the integrity of letters (not unlike many of Susan Howe’s collages in That This), we are brought to consider the implications of “reading” the fold itself as a moment of linguistic breakdown, a crisis of legibility, and a radical change in readerly engagement and the rules of chronology.

Like a burst of static on the radio that cuts through narrative and releases you elsewhere and elsewhen after it dissipates, Baum’s folds separate upright, left-justified beginnings of lines from their cliff-dangling, sideways-hanging consequences. To me, this resembles how disparate temporalities and geographies are often stitched together in memory. For instance, I recall how I began my adult life (2016, Ohio, steeped in irascible swing state politics) and I make note of where I’ve landed (2026, California, a return to my once sworn-off hometown and its gentler winters). As I move from one moment to the other, I’ll interpolate that space and time not with a clear chronology of dates and places, but with chicken scratches and static—things that are simply not translatable to the locutionary (in this autobiographical example: a swell of forgotten, now-illegible, and aborted intentions; inscrutable reasoning; late nights to the point of delirium; a vague blur).

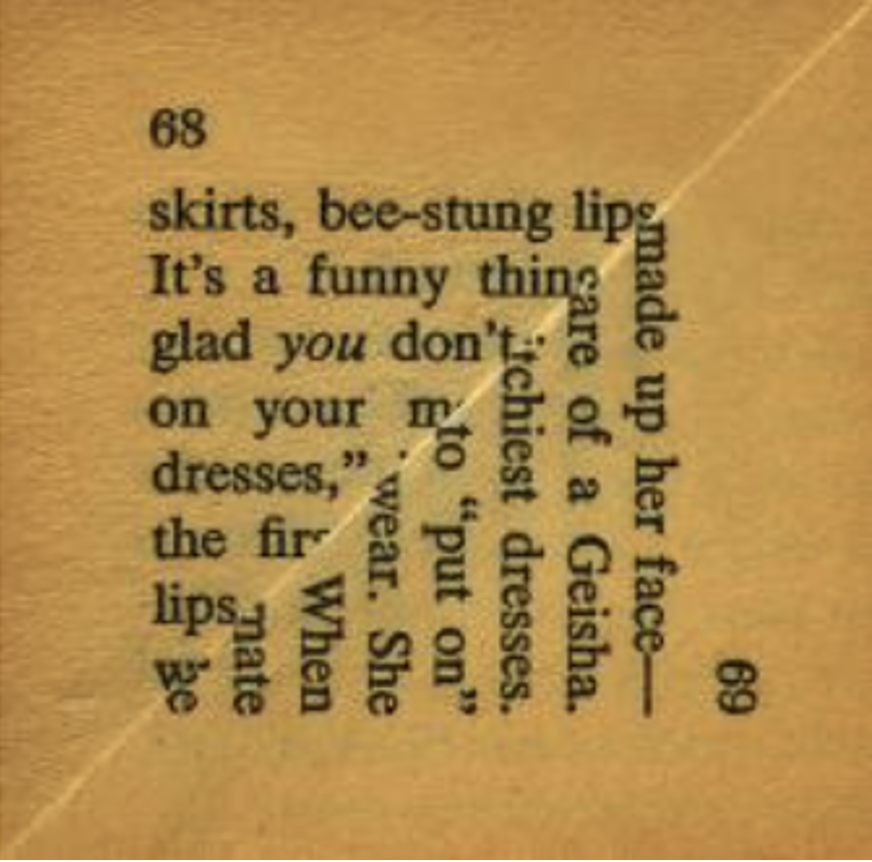

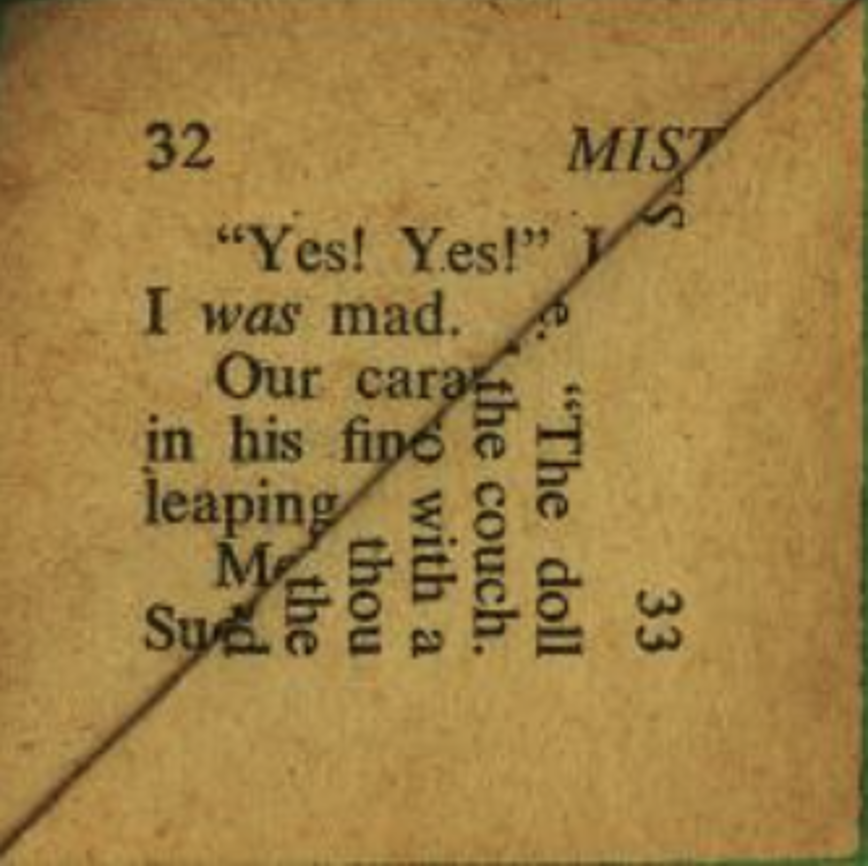

What if, just as much as we understand Baum’s dog-eared fold as a seam connecting disparate sections of text, we also see it as a ray of chaos cutting through the texts, signaling a moment (or process) of reorganization of language, sense, and desire? I cannot help but stumble into a loss of conventional communication along the dog-eared fold; it creates a strain of fragmented letters (letter-adjacent limbs)—insinuations of the once whole. In “Fallout,” for instance, the character following “lovely” is suspended in liminality between meaning and nonmeaning: [2]

Fallout,

2010

Eclipsed by the fold, it inhabits a kind of Schrödingerian possibility, looking enough like a “v” and a “y” and even the first divot of a “w” to be—for us as readers—all three. From there, it could express so many things—a modest sampling: lovely vines, lovely ventricles, lovely yesterdays, lovely yo-yos, lovely wedding days, lovely wet beds. The fold explodes the potential avenues for the partial-“v,” but it also rescinds definite meaning; it grants everything along its bulldozing path the quality of infinity.

With a loss of definitive meaning and legibility along the fold, the term “asemic” comes to mind, although Baum’s letter fragments are a far cry from the non-language of Renee Gladman’s Plans for Sentences. Nor do they quite adhere to Peter Schweger’s description of the asemic (writing that “asks us to conceptualize what we are seeing—not reading [...and] frees us from the structuration of lines of thought” through contours that represent thought processes and abstract ideas of writing without content. [3]

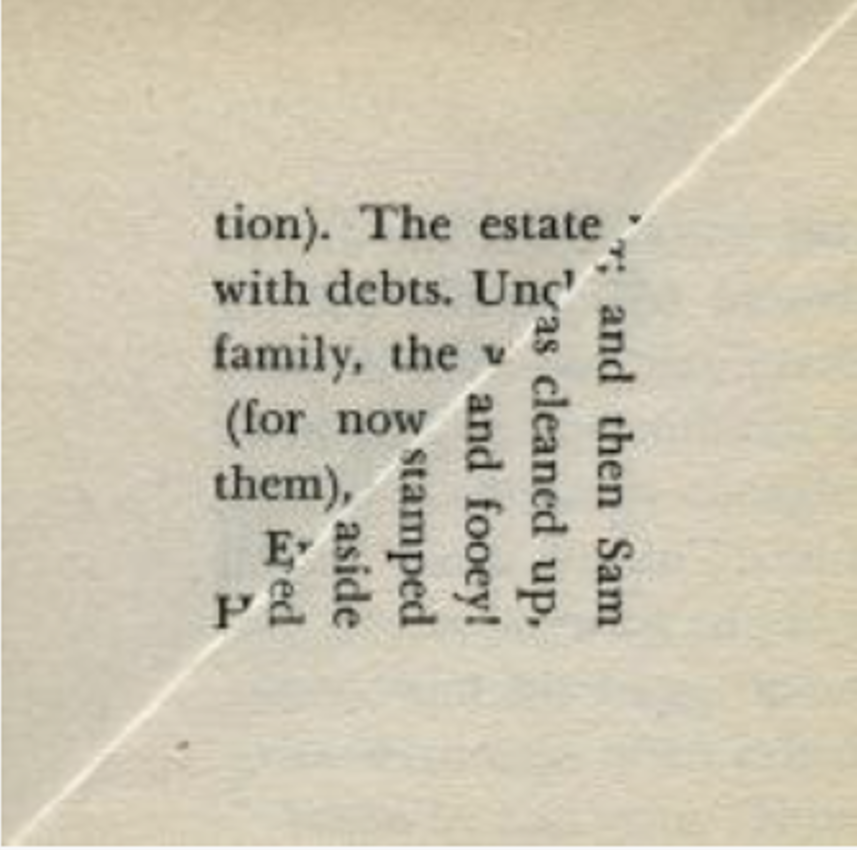

Still, even falling short of asemic, these dog ear folds disrupt conventional communication. While they indeed create a new, interesting synergy between the horizontal and vertical lines, what I’m most interested in is reading and riding along this letter-slicing diagonal line that demarcates a horizontal “before” text from vertical “after” text. I think Dog Ear may be asking me to round out—or more appropriately “square off”—these chevrons of text towards something consummate; the squareness of the form insinuates the possibility of perfection amid two disparate, partial passages. Squareness connotes evenness and symmetry—fairness and predictability. Because squares are calculable and knowable, I’m brought to falsely trust that these squares will contain two reconcilable halves. In these dog ears, the latter text may be part of the same book, but it arrives as a non-sequitur without the decorum of introduction—in mid-air without the runway, and with no syntactical allegiance to its predecessor. It has no past—or its past often feels unrecognizable, unrecallable.

Folds, in the context of physical books, do not always betray so impetuously, of course. In Lisa Robertson’s essay “Time in the Codex”, she meditates on “[inhabiting] its joinery”—recounting a devotion to the codex’s bounded, unified materiality. [4] At its folds, the codex grows a spine, ushering its disparateness into an aggregate. It holds together at its folds. Not quite so in Dog Ear. Even as Baum’s folds insinuate connection, they don’t do so in service of chronology and continuity as the codex does. Instead, they deny the leftmost text its future and the rightmost its past—less an act of cohesion, more one of collapse. Baum’s folds “fold” in the sense of bankruptcy, insolvency, crash. After “Fallout’s” meta-reference to the way its text literally meets a limit at the fold (at the line “known limits”), a single closing parenthesis—without a trace of its opening counterpart—holds up a falling language: a slain, supine “d”.[5]Here, I encounter an unsparing violence; the fold has redacted the parenthesis’s antecedent—its origin, its complement, the one that prescribed its purpose—leaving us a gesture of closing with no trace of its beginning, a consequence without cause.

In the time that passed between my beginning this essay and completing it, my father’s health turned from picture perfect to surprise cancer, virtually overnight. Sharp as the downturning of a page’s corner, unsparing as the rupture of a fold. His rapid decline was as intelligible as static and as articulate as white noise. His death, mere months later, seemed apropos of a completely different beginning, a more overtly carcinogenic life, decades of a different skin. It was as if wires had crossed—as if, across the slash of a dog ear and a diagnosis, two wrongly contiguous narratives became one, and the syntax of our comfortable reality was amputated, and then appended, by the putrid syntax of another.

Geisha, 2010

The Plant World, 2010

Debts, 2009

Mad, 2009

When I talk about my encounter with violence across the dog ear, this is the violence I mean: the denial of beginnings their endings, of conclusions their prologues, and of the togetherness of things that rely on the presence of one another to have meaning individually. When “Fallout’s” dog ear slices through text, it orphans a closing parenthesis from its parent—the open-mouthed punctuation mark “ ( ” that first announced the intimate whisper between them; the one who first broke from the grand narrative of the text to initiate a separate language; the one who said, What we hold may be an afterthought—an aside—but it is crucial enough to interrupt this entire world.

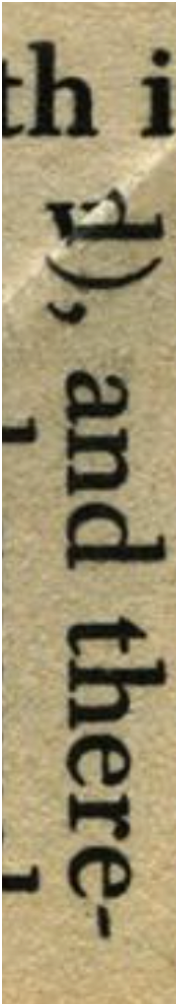

In committing its fold, “Fallout” presents us with multiple crises: the indeterminacy of origins and the dissolution of companionship. Without its opener, the end parenthesis has no rein on the hushed knowledge the two of them once strung together. It holds nothing secure. A once cordoned-off language spills back into the past, uncradled and uncontained, and the hunt for the origin of this language would send us backtracking forever. Impaired from its decreed purpose, the second bracket becomes—in keeping with the heightened tactility of Baum’s work—an askew, defamiliarized, ultimately renewed material. It resembles something like a bowl holding (not an intimate language, but) a gashed, half-bellied “d.”[6]The conjunction that follows, “and,” joins this shard of language to a line that is fated to repeat these cycles of severance and interruption.[7]At the line’s end, a hyphen reaches out from the word “there,” kept from wholeness by the margin’s territory, yet intending to connect itself to its constituent in the next line.[8]But this hope is voided by the dog ear. The next line—the one that “there-” anticipated—is not there. Instead, some unfamiliar hand will join it.

from “Fallout, 2010”

These are crises enacted by poetic hapticity: to lose one’s beginnings, to lose one’s other half—the father, the twin, the being that is the mirror to and the completion of oneself. Crisis is spelled out by the disembodied, asemic-adjacent shards of letters that spin out along the fold, creating a line that doesn’t bear a semantic message, but that nonetheless clearly signals something: sudden, radical change. “Reading” that rupture, I recognize the way that seemingly distant, incongruous narratives can exist intimately within the same narrative—within the same life—residing on either side of interruption: the dog-eared line of crisis, betrayal, reset, and reinvention.

Notes

[1] “Photographs from Dog Ear.” Jacket2, 9 March 2011, https://jacket2.org/galleries/photographs-dog-ear.

[2] “Photographs from Dog Ear.”

[3] Peter Schwenger, Asemic: The Art of Writing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019, 7.

[4] Lisa Robertson, Nilling: Prose Essays on Noise, Pornography, the Codex, Melancholy, Lucretius, Folds, Cities and Related Aporias (Toronto: BookTh*g, 2012), 14.

[5] “Photographs from Dog Ear.”

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

Works Cited

Baum, Erica. “Photographs from Dog Ear.” Jacket2. 9 March 2011. https://jacket2.org/galleries/photographs-dog-ear.

Baum, Erica, Goldsmith, Kenneth, and Gross, Béatrice. Dog Ear. 1st ed. Brooklyn, New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2011.

Gladman, Renee. Plans for Sentences. 1st ed. Seattle: Wave Books, 2022.

Howe, Susan. That This. New York: New Directions, 2010.

Robertson, Lisa. Nilling: Prose Essays on Noise, Pornography, the Codex, Melancholy, Lucretius, Folds, Cities and Related Aporias. 1st ed. Department of Critical Thought; No. 6. Toronto: BookThug, 2012.

Schwenger, Peter. Asemic: The Art of Writing. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.