On Dana Ward’s “The Squeakquel”: Or, the Kind of Email I Mean

Some people say letter writing is dying. In the New York Times, Dwight Garner bemoans

this loss for lovers of literature: no more diving into the volumes of a

writer’s collected correspondence to haul up proffered intimacies, gossip, frustrations,

or simply the minutiae of daily life. [1] Yet Garner goes further,

arguing that the death of letter writing is a loss not only for literary

history, but human sociality writ large. Like most people nowadays, he doesn’t

exchange long letters with his friends, and finds nothing satisfactory as a

replacement. He cops to sending occasional “big, juicy emails,” but doesn’t think

much of it: for Garner, email is a self-evidently inadequate substitute.

I love big, juicy emails. To me it makes no sense to claim that emails are an inadequate vector for social life. They comprise the fabric of social life itself! Maybe the sensory experience is changed—no more ripping open the envelope, unfolding the paper, deciphering the messy and familiar handwriting—but there’s nothing fatal here. The only inadequacies to be found in emails are our own, the ones that lie and wait to be scribbled down on scraps of paper or thumbed into notes apps, then piled all together at the day’s end, half-reread while being bullied by sleep before saying “fuck it” and hitting send.

The other reason I love emails is because I can’t spend very long thinking about them without thinking about the ending of Dana Ward’s poem “The Squeakquel,” the final poem in his 2013 collection The Crisis of Infinite Worlds. “The Squeakquel” is a long poem, thirty pages in prose, and is about, among much else: parenthood, friendship, the talismanic power of objects, poetry as a kind of lifeworld, a goofy séance, the 2009 film Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakquel, the relationship between art and life, the internet of people (extant utopia), the internet of things (hellish utopia), a prodigal scarf, “the complete incineration of commodity relations,” and email. The poem ends:

My friend Jon pointed out to me that Ward’s poetry, especially his poems in prose, function as a sort of macrolyric. Their flights into figuration, instead of being tethered to the line or sentence, peal out wildly, blowing through sentences or entire paragraphs, leaving a trail of busted syntax in their wake. Gravity’s in a weakened state; the figure’s feet won’t touch the ground. If the archetypal ending gesture of a lyric poem is the sharp inhale followed by a radical opening, then it may be that the “The Squeakquel” performs this gesture on an oversized scale. It gives us a volta the length of a paragraph. This paragraph—which is occasioned by an email sharing news of the lost scarf’s return, and which, if it isn’t already obvious, I love utterly, in a judgment-clouding way—erupts out of the softness of the previous lines to race toward a state of visceral longing and deep confusion. To elaborate:

1. Some people say email is dying. The early 2010s were marked by the persistent refrain and insufferable handwringing about whether or not poetry was dead. Is a poem an email? Is an email a poem? Not every email, but you know the kind of email I mean. This paragraph opens by inciting a collapse between email and poem that the remaining sentences follow from. Some people say email is dead, but you know the kind of poetry I mean.

2. Ward distinguishes between two types of emails: the ideal and the placeholder. The ideal is the one his friend deserves—a long note full of incredible insights, thrills, & intimate disclosures that will attempt to diminish some of the distance that’s between you—but that isn’t this email. This is just one of those placeholder emails, and its purpose is to stand in for the email that it knows it ought to be—it doesn’t have enough time to do the other thing, though one day it will. When does one day come? When will I stop putting off writing the poem I know I need to write?

3. What I left out about the emails: the ideal email will only attempt to diminish the distance—if it were ever written, it would only amplify the cruelty of that distance. So what the ideal email does, if it succeeds at what it sets out to do, is just call attention to that distance, like sticking a finger in a wound. This is because—and I think this is what Ward means—that distance is irremediable. Though a lyric poem’s animating force is the desire to close that distance, you know and I know that when the end comes that distance will still be here, barely changed, simply louder and more cruel.

4. One thing poetry is: a technique for living in the fallout of distance’s cruelty (preemptive afterlife).

5. There is something special about the placeholder email and that’s its something else. In writing itself into the shape of an IOU, it makes a promise that disfigures the absence with a vow. This vow is powerful, more powerful than what the ideal email would do. In disfiguring absence it holds it back; the cruelty of distance is kept at bay. But this vow pulls off a second something else: it denatures the poem’s bonds to syntax and determinate meaning. From this moment onward, the poem spirals out into a kind of imagistic thought that exceeds itself, showing only traces of the sense that glows inside the screen.

6. Then the poem incubates incubates incubates, residing in a zone of latency and heat, waiting to hatch (again—when does one day come?) and take the shape it promised. But the warmth of this potential is undermined and thrown when figuration strikes and the email finds itself instead like Sleeping Beauty in her coffin of frosting & breath. This simile is at once buoyed by enchantment and punctured by death. Frosting conjures not only images of elegant, fondant-laden cakes, but the anti-incubation of Sleeping Beauty’s icy breath condensing and freezing on the interior of her coffin. A respiring death, or a life devoid of warmth.

7. Not forever, simply waiting—suspended in some eerie frozenness adjacent to a thaw. This is the power of the something else an email does: this eerie frozenness is all potential energy, and the fumes it emits keep the breath going and heart beating in anticipation of the prince’s kiss that would banish distance forever.

8. I mentioned above those moments in Ward’s poems when the ligature of syntax slackens and the poem tumbles past the meaning it rushes to make. This effect is fully realized at the paragraph’s end: it exceeds its words like love but weirdly keeps losing its feeling for existence. This moment confounds me. Why does the poem/email lose its feeling if it’s adjacent to a thaw, when feeling creeps back in? And keeps losing—as in, it loses it and regains it? Or is this loss a constant condition, a lifestyle? And that weirdly! Is the loss itself weird? The fact of the loss? Each rereading brings new questions and no answers, and whatever it is that the end of the traditional lyric promises—catharsis, knowledge, paradise, death—doesn’t come. We’re still in our coffin waiting for the kiss, it’s nowhere near, the poem’s about to end but then:

9. More Soon. The sign-off certifies that email and poem are one, and enacts the promise that disfigures the absence with a vow. We know that what we’ve just finished reading—this final page, “The Squeakquel,” maybe the whole of The Crisis of Infinite Worlds—is only a placeholder. It isn’t the poem or the email we’ve been waiting for. But this is not a bad thing. Instead of giving us the kiss that would awaken us to the ice forming on the inside of our coffin, it lets us sleep and lets us dream (remain living), running off the fumes of the promise that the real thing is coming soon.

10. And by soon I mean the end of time.

An email to Piers, Yu, Kyra, and Amy from 2015

Some people say friendship is dying. When I catch up with an old friend from whom I’ve been separated by time or distance or both, I’m frequently haunted by the sense that the true subject of our conversation—the true substance of our friendship—is this very separation and the change it has wrought on us. In these moments each memory, insight, anecdote, joke, advice, kindness, etc. is just the shape that separation takes; behind it hides the cruelty of the distance. With time, though, these moments reshape themselves into something like Ward’s placeholder. Within the separation that has become the substance of some of my closest friendships incubates incubates incubates the promise of a later unity. Sometimes this promise feels illusory, foolish—whatever wholeness I want the world to inflict upon me is tetherless, a desire with no object. This distance between us isn’t curable, but I don’t know that yet. I know only that it’s lying here just like Sleeping Beauty in her coffin of frosting & breath. Awaiting what? The kiss of the prince that cures loneliness by ending time?

I confuse friendships for poems. I confuse poems for emails.

I don’t think email is dying. I have a group of friends with whom, since college ended, I’ve been sporadically exchanging emails, migrating from thread to thread. As the years have passed, these threads have shifted from hubs of conversation to spaces for belated life updates (big, juicy emails) (you know the kind of email I mean). Sometimes our (my) emails are shameless in their aspiring toward this shape. When I reread them they’re often embarrassing in their earnestness, indulgence, and compulsive self-awareness. But this excess is what I love about long emails so much, reading them even more than writing them. Not just sharing thoughts and what’s happening and each other’s words across distance, but gently or not-so-gently embarrassing yourself before people you love and miss. In this way it becomes a placeholder: a covenant for future wholeness. A promise that disfigures the absence with a vow. When things finally aren’t so crazy. When we can finally be together again. When that kiss finally lands. When time finally ends.

More soon.

Works Cited

[1] Dwight Garner, “Mourning the Letters That Will No Longer Be Written, and Remembering the Great Ones That Were,” The New York Times, June 17, 2020. <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/17/books/art-of-writing-letters.html>.

[2] Dana Ward, The Crisis of Infinite Worlds, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Futurepoem Books, 2014), 145.

I love big, juicy emails. To me it makes no sense to claim that emails are an inadequate vector for social life. They comprise the fabric of social life itself! Maybe the sensory experience is changed—no more ripping open the envelope, unfolding the paper, deciphering the messy and familiar handwriting—but there’s nothing fatal here. The only inadequacies to be found in emails are our own, the ones that lie and wait to be scribbled down on scraps of paper or thumbed into notes apps, then piled all together at the day’s end, half-reread while being bullied by sleep before saying “fuck it” and hitting send.

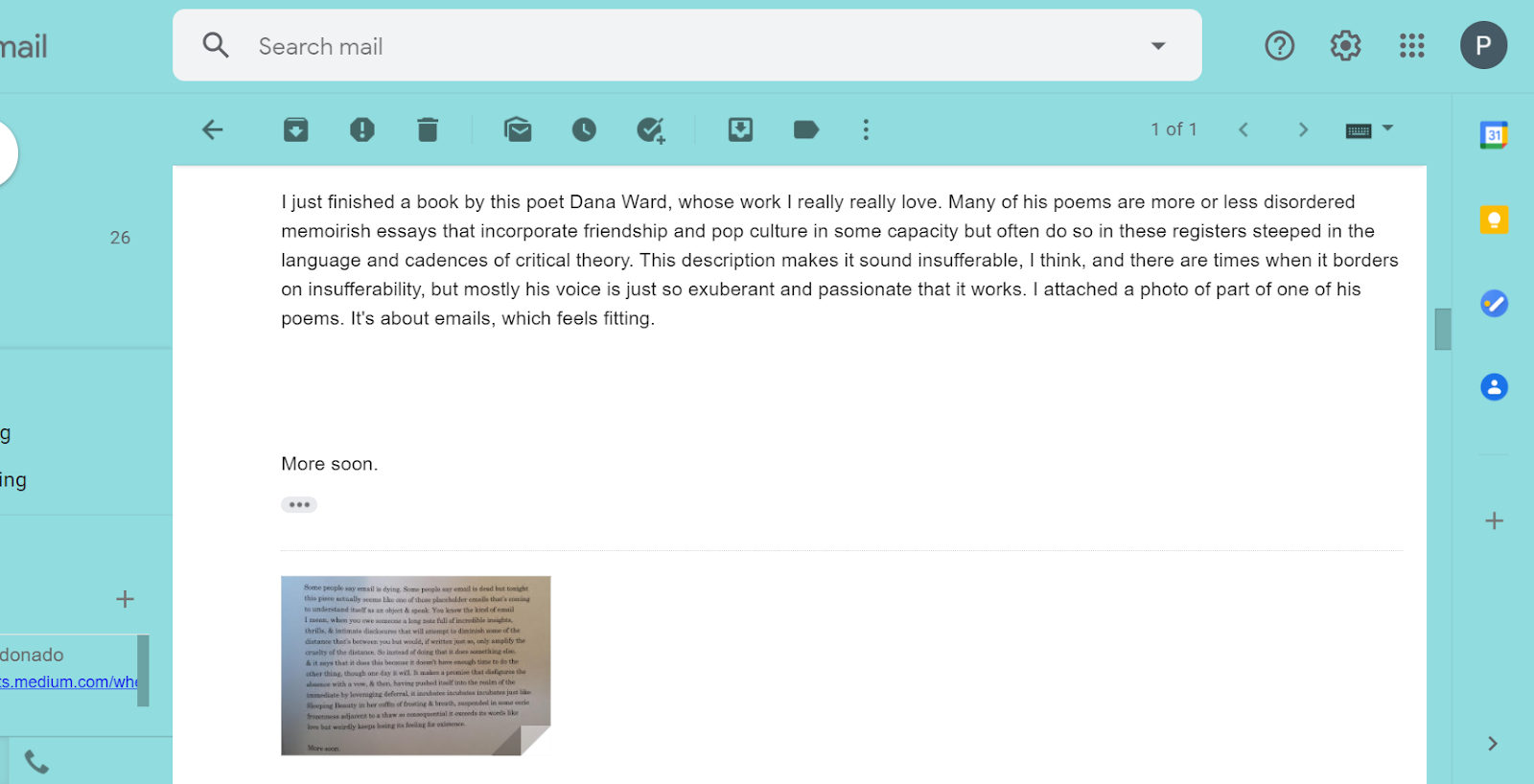

The other reason I love emails is because I can’t spend very long thinking about them without thinking about the ending of Dana Ward’s poem “The Squeakquel,” the final poem in his 2013 collection The Crisis of Infinite Worlds. “The Squeakquel” is a long poem, thirty pages in prose, and is about, among much else: parenthood, friendship, the talismanic power of objects, poetry as a kind of lifeworld, a goofy séance, the 2009 film Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakquel, the relationship between art and life, the internet of people (extant utopia), the internet of things (hellish utopia), a prodigal scarf, “the complete incineration of commodity relations,” and email. The poem ends:

Some people say email is dying. Some people say email is dead but tonight this piece actually feels like one of those placeholder emails that’s coming to understand itself as an object & speak. You know the kind of email I mean, when you owe someone a long note full of incredible insights, thrills, & intimate disclosures that will attempt to diminish some of the distance that’s between you but would, if written just so, only amplify the cruelty of the distance. So instead of doing that it does something else, & it says that it does this because it doesn’t have enough time to do the other thing, though one day it will. It makes a promise that disfigures the absence with a vow, & then, having pushed itself into the realm of the immediate by leveraging deferral, it incubates incubates incubates just like Sleeping Beauty in her coffin of frosting & breath, suspended in some eerie frozenness adjacent to a thaw so consequential it exceeds its words like love but weirdly keeps losing its feeling for existence.

More soon. [2]

My friend Jon pointed out to me that Ward’s poetry, especially his poems in prose, function as a sort of macrolyric. Their flights into figuration, instead of being tethered to the line or sentence, peal out wildly, blowing through sentences or entire paragraphs, leaving a trail of busted syntax in their wake. Gravity’s in a weakened state; the figure’s feet won’t touch the ground. If the archetypal ending gesture of a lyric poem is the sharp inhale followed by a radical opening, then it may be that the “The Squeakquel” performs this gesture on an oversized scale. It gives us a volta the length of a paragraph. This paragraph—which is occasioned by an email sharing news of the lost scarf’s return, and which, if it isn’t already obvious, I love utterly, in a judgment-clouding way—erupts out of the softness of the previous lines to race toward a state of visceral longing and deep confusion. To elaborate:

1. Some people say email is dying. The early 2010s were marked by the persistent refrain and insufferable handwringing about whether or not poetry was dead. Is a poem an email? Is an email a poem? Not every email, but you know the kind of email I mean. This paragraph opens by inciting a collapse between email and poem that the remaining sentences follow from. Some people say email is dead, but you know the kind of poetry I mean.

2. Ward distinguishes between two types of emails: the ideal and the placeholder. The ideal is the one his friend deserves—a long note full of incredible insights, thrills, & intimate disclosures that will attempt to diminish some of the distance that’s between you—but that isn’t this email. This is just one of those placeholder emails, and its purpose is to stand in for the email that it knows it ought to be—it doesn’t have enough time to do the other thing, though one day it will. When does one day come? When will I stop putting off writing the poem I know I need to write?

3. What I left out about the emails: the ideal email will only attempt to diminish the distance—if it were ever written, it would only amplify the cruelty of that distance. So what the ideal email does, if it succeeds at what it sets out to do, is just call attention to that distance, like sticking a finger in a wound. This is because—and I think this is what Ward means—that distance is irremediable. Though a lyric poem’s animating force is the desire to close that distance, you know and I know that when the end comes that distance will still be here, barely changed, simply louder and more cruel.

4. One thing poetry is: a technique for living in the fallout of distance’s cruelty (preemptive afterlife).

5. There is something special about the placeholder email and that’s its something else. In writing itself into the shape of an IOU, it makes a promise that disfigures the absence with a vow. This vow is powerful, more powerful than what the ideal email would do. In disfiguring absence it holds it back; the cruelty of distance is kept at bay. But this vow pulls off a second something else: it denatures the poem’s bonds to syntax and determinate meaning. From this moment onward, the poem spirals out into a kind of imagistic thought that exceeds itself, showing only traces of the sense that glows inside the screen.

6. Then the poem incubates incubates incubates, residing in a zone of latency and heat, waiting to hatch (again—when does one day come?) and take the shape it promised. But the warmth of this potential is undermined and thrown when figuration strikes and the email finds itself instead like Sleeping Beauty in her coffin of frosting & breath. This simile is at once buoyed by enchantment and punctured by death. Frosting conjures not only images of elegant, fondant-laden cakes, but the anti-incubation of Sleeping Beauty’s icy breath condensing and freezing on the interior of her coffin. A respiring death, or a life devoid of warmth.

7. Not forever, simply waiting—suspended in some eerie frozenness adjacent to a thaw. This is the power of the something else an email does: this eerie frozenness is all potential energy, and the fumes it emits keep the breath going and heart beating in anticipation of the prince’s kiss that would banish distance forever.

8. I mentioned above those moments in Ward’s poems when the ligature of syntax slackens and the poem tumbles past the meaning it rushes to make. This effect is fully realized at the paragraph’s end: it exceeds its words like love but weirdly keeps losing its feeling for existence. This moment confounds me. Why does the poem/email lose its feeling if it’s adjacent to a thaw, when feeling creeps back in? And keeps losing—as in, it loses it and regains it? Or is this loss a constant condition, a lifestyle? And that weirdly! Is the loss itself weird? The fact of the loss? Each rereading brings new questions and no answers, and whatever it is that the end of the traditional lyric promises—catharsis, knowledge, paradise, death—doesn’t come. We’re still in our coffin waiting for the kiss, it’s nowhere near, the poem’s about to end but then:

9. More Soon. The sign-off certifies that email and poem are one, and enacts the promise that disfigures the absence with a vow. We know that what we’ve just finished reading—this final page, “The Squeakquel,” maybe the whole of The Crisis of Infinite Worlds—is only a placeholder. It isn’t the poem or the email we’ve been waiting for. But this is not a bad thing. Instead of giving us the kiss that would awaken us to the ice forming on the inside of our coffin, it lets us sleep and lets us dream (remain living), running off the fumes of the promise that the real thing is coming soon.

10. And by soon I mean the end of time.

An email to Piers, Yu, Kyra, and Amy from 2015

Some people say friendship is dying. When I catch up with an old friend from whom I’ve been separated by time or distance or both, I’m frequently haunted by the sense that the true subject of our conversation—the true substance of our friendship—is this very separation and the change it has wrought on us. In these moments each memory, insight, anecdote, joke, advice, kindness, etc. is just the shape that separation takes; behind it hides the cruelty of the distance. With time, though, these moments reshape themselves into something like Ward’s placeholder. Within the separation that has become the substance of some of my closest friendships incubates incubates incubates the promise of a later unity. Sometimes this promise feels illusory, foolish—whatever wholeness I want the world to inflict upon me is tetherless, a desire with no object. This distance between us isn’t curable, but I don’t know that yet. I know only that it’s lying here just like Sleeping Beauty in her coffin of frosting & breath. Awaiting what? The kiss of the prince that cures loneliness by ending time?

I confuse friendships for poems. I confuse poems for emails.

I don’t think email is dying. I have a group of friends with whom, since college ended, I’ve been sporadically exchanging emails, migrating from thread to thread. As the years have passed, these threads have shifted from hubs of conversation to spaces for belated life updates (big, juicy emails) (you know the kind of email I mean). Sometimes our (my) emails are shameless in their aspiring toward this shape. When I reread them they’re often embarrassing in their earnestness, indulgence, and compulsive self-awareness. But this excess is what I love about long emails so much, reading them even more than writing them. Not just sharing thoughts and what’s happening and each other’s words across distance, but gently or not-so-gently embarrassing yourself before people you love and miss. In this way it becomes a placeholder: a covenant for future wholeness. A promise that disfigures the absence with a vow. When things finally aren’t so crazy. When we can finally be together again. When that kiss finally lands. When time finally ends.

More soon.

Works Cited

[1] Dwight Garner, “Mourning the Letters That Will No Longer Be Written, and Remembering the Great Ones That Were,” The New York Times, June 17, 2020. <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/17/books/art-of-writing-letters.html>.

[2] Dana Ward, The Crisis of Infinite Worlds, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Futurepoem Books, 2014), 145.